Some days start out better than others. Like the day I woke up to find an e-mail from the manager of the Iwashita Collection museum in Japan, asking if I’d like to be the first media representative in the world to see the full 500-strong bike hoard. A very quick ‘yes’ in response, and plans were made. So it was that a few weeks later, I stood outside a rather nondescript building in the stunning Kyushu countryside, waiting to see the first of three sets of classic motorbikes.

I say three as, like most major collections, Mr. Iwashita’s bikes are never all on show at once. In fact, only about 150 of his estimated 500 bikes (including possibly the largest collection of Japanese classics on the planet) is ever visible to the public. One reason is that he simply hasn’t got around to restoring the majority, but the biggest reason is space. While the collection’s location in rural Japan means the main public museum is hardly small, it can’t contain all 500 bikes, with the rest stored in two separate warehouses dotted around the prefecture.

So, starting with the public collection, which is an amazing mix of machines from all around the world, I began exploring what bikes Mr. Iwashita had.

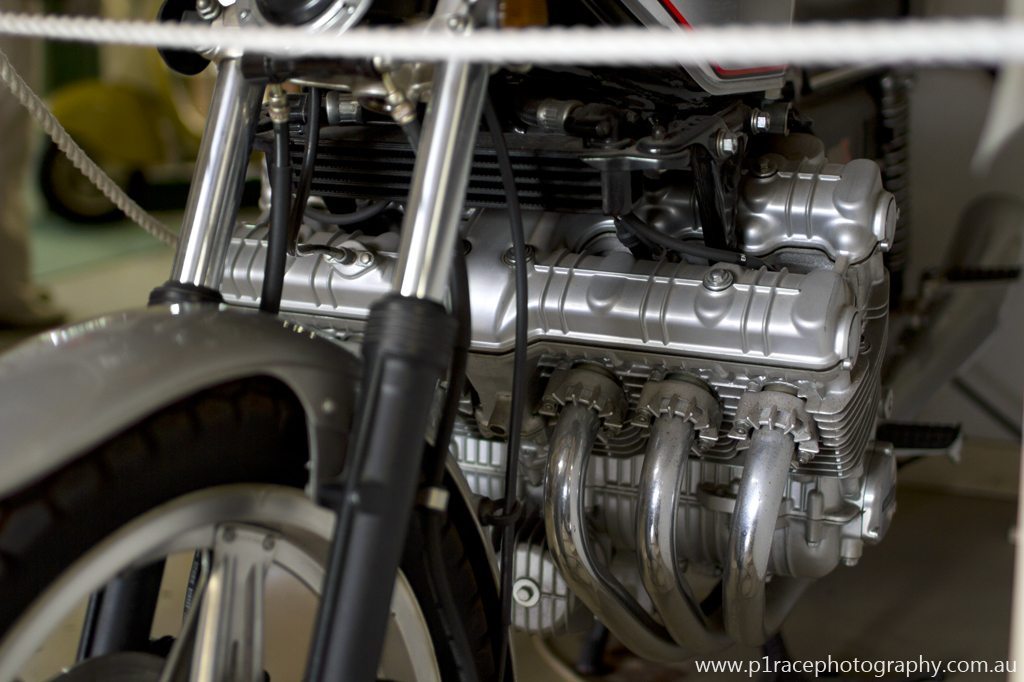

It seems apt to begin the tour with this – an example of the first ever motorised bicycle Honda built. With its rod brakes, engine that looks more steampunk than internal combustion and sprung leather saddle, you could hardly get more removed from the super-fast, sleek bikes the giant manufactures today, but this is where it all started. It was amazing and humbling to see.

Indeed, Mr. Iwashita has quite the Honda collection as part of his museum. Including examples of the second…

… and third models the company ever produced as well. What was fascinating to me was not just how different these things were to what we know now, but how much evolution occurred in just the first three generations. From essentially a shopping bike with a motor in it, to a more specialised-looking machine that’s a bit more familiar, to a monocoque frame, all in three models. Stunning. Notice the evolution of the badge, as well. While you can’t see it, there’s a small ‘Dream’ subtitle, denoting the model name, below the Honda logo, too. While younger bike fans may think this ‘Dreams’ thing is just modern marketing spiel, there’s a lot more history to it than that.

Mr. Iwashita also has pretty much every other significant classic, commercially-available Honda model on display in this section as well. That includes the Dream and CB models in the picture above, an example of the six-cylinder CBX…

… the actual XLR-250 that circumnavigated the globe solo under Toshiyuki Araki, complete with memorabilia …

… and the cleanest-looking Gorilla I’ve ever seen. (Pun most definitely intended).

For the speed freaks, you could even find a Honda Benly Super Sports CB92 (below). For its day, considering its 125cc engine, it was quite the rapid beasty, capable of 17-second quarter miles. Hardly blow-your-socks-off territory today, but not bad for 1959.

Continuing on with Japanese history, you had a wide range of other manufacturers and models represented.

Some were perhaps a little less known than others, such as the Noritsu KB-2 and Suzuki Diamond Free F60 (although the F60 was actually a famous racing bike of its day).

Others, while huge at the time, you may not have heard of at all, like Cabton. One of the top Japanese manufacturers in its day, Cabton was actually an acronym for Come And Buy To Osaka Nakagawa, referencing the Osaka suburb where the bikes were made. Questionable English aside, its British-style four-strokes were big sellers, ranking them alongside the likes of Meguro…

… who were also well-represented. For those who don’t know, Meguro was once Japan’s second-biggest bike manufacturer, outsold only by Honda. It was also a highly prestigious brand, supplying bikes like the one below to the police and other government departments.

These days, people might know Meguro better by the name Kawasaki, which bought the brand after a run of poorly-judged lightweight models and a year-long strike caused Meguro to become financially unviable. They had worked in a partnership beforehand, though, so it was more rescue than giant gobbling up a weakened enemy.

For Yamaha fans, this might be the crown jewel of the collection, though – an example of the 125 YA-1 – Yamaha’s first motorbike. Famous not just for being a successful racing machine right off the bat, but also introducing the clutch-in, kick-start system used on virtually every bike afterwards until the age of electronic ignition, seeing the YA-1 was again a humbling experience.

Before I move onto non-Japanese brands, I thought it might be interesting to see a few JDM oddities, too. Like this Nissan motorised bicycle. Yup, while they never took off, Nissan did have a go at making two-wheeled models as well.

Of course, it wasn’t just Nissan that had an interesting past. Few people today know that Mazda got its start in trikes, for example.

Finally, I couldn’t resist a shot of the super-cute Marusho Baby Lilac. With its unique headlamp-on-tank styling and apparently amazing ride comfort, there’s no wonder it was a best seller back in 1953.

Despite its sizeable Japanese section, the Iwashita Collection was not all about domestic bikes, though. You had pretty impressive sections covering German and Swiss brands…

…including this Condor 580 Military, while off to the left of that was the excellent British section.

Featuring marques like BSA, Royal Enfield and Douglas, you even had a Sturmey Archer Nestoria thrown in for good measure. (Far left).

Of course, you couldn’t go without some Nortons as well. Like the German section, note the four-wheeled ‘accessory’ in the background!

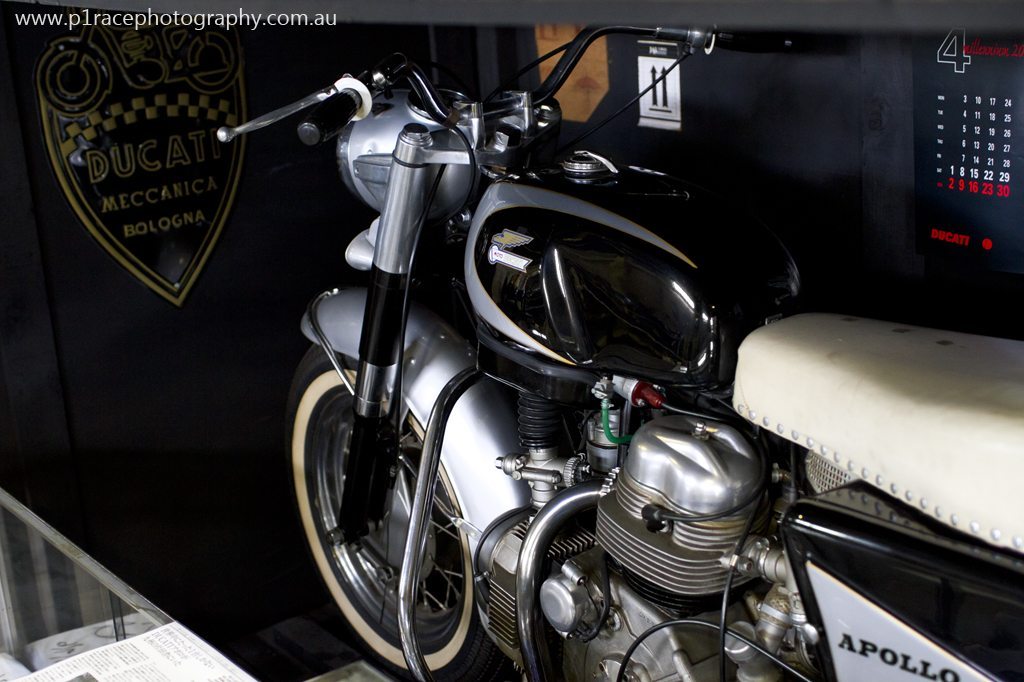

I was a little puzzled by the lack of Italian motorbikes until I remembered the museum’s centrepiece, and its cost.

The Ducati Apollo prototype, valued at time of purchase at US$1 million, may have taken all the remaining budget the Italian section had. One of two made, the other’s location or status is not known, and might well have been destroyed, following the project’s lack of success and subsequent dismantling. Initially designed to compete with Harley Davidson for the American police bike market, the Apollo project came about after a proposal from US Ducati importer the Berliner Motor Corporation. However, it was beset with problems throughout, almost exclusively to do with its tyre use. Or should I say abuse. Putting out 100hp from its 1256cc V4, the bike destroyed every set of tyres fitted to it, even ones specially made for it. (For comparison, the equivalent Harley police bike made 55hp). One test rider said he was lucky to be alive after a high-speed tyre disintegration on the Autostrada.

Ducati did keep reducing its power in a hope of making the project work, but by the time the Apollo was ready, other brands from Britain and Germany had more powerful bikes that did not eat tyres. In the end, while there was hope of keeping the project alive, the Italian government, which owned Ducati at the time, pulled its funding and that was that. The remaining prototype was purchased some time ago by Mr Iwashita and, one stint in the Museo Ducati aside, has remained here ever since.

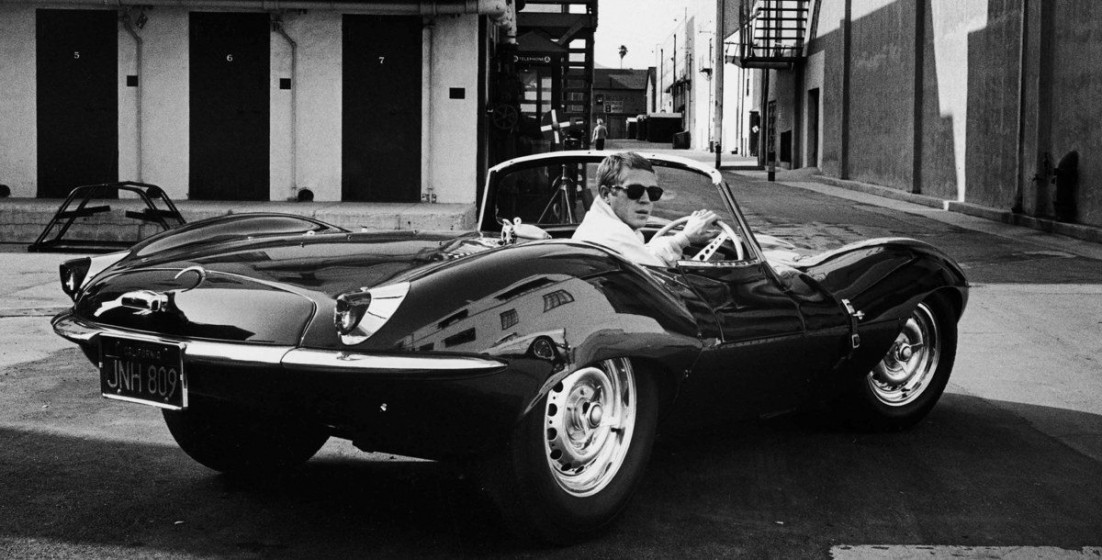

Skipping across to another section of the museum, I found its other major attraction – an Indian Chief ’74 sidecar once owned by Steve McQueen.

This stunning piece of art sat amongst its contemporaries, including two other Indians and some Harleys, showing off the beauty of American iron.

At the end of the American aisle sat another Harley, which may not have looked much, but came with a great history.

This 1917 JD was originally owned by an Australian, who bought it new in his teens and kept it his whole life, using it lovingly and only passing it on when he himself passed away. It was then purchased by a Japanese man working in Australia at the time, and eventually made its way to the museum via him. Some may argue that a one-owner motorbike is nothing special. Given it was a lifelong love affair, though, I’d argue differently.

One final item of note for me in the American section came in the form of another sidecar, this time from south of the border. This Brazilian Amazonas is probably one of the few four-seat outfits ever made, and makes sense as a method of getting a family around on a budget. ET, though? I have no idea.

Heading up to the mezzanine, I got to see the small, but well-chosen selection of racing bikes. Some may recognise the red number 23 model from its GP days, ridden as it was by one Kenny Roberts.

It even has his signature from when the man himself came to the museum and sat astride his old chariot.

Truth be told, it’s an amazing sight up close. But perhaps not for the reasons one might think. Whilst it’s always awe-inspiring to see old racing metal, for me, it was startling to see how agricultural it all looked. In reality, I don’t doubt any current 600cc sport bike would handily outdo it. That’s not to take anything away from it achievements at the time, though. And no 600cc sport bike will have the history and competition pedigree this has.

Other highlights included this stunning pair of Honda machines at the far end of the mezzanine, the red Cub Racing model bearing the signature of Nobby Clark himself.

Oh, and how about this stunning Yoshimura Honda (yes, Honda) CB72? Honda really should make something that looks like this again, even if it’s just a cafe racer.

Finally, Mr. Iwashita had the good sense to get himself a Velocette KTT MKIV, otherwise known as the first bike with today’s standard pedal shift system.

Before we leave the public collection for the hidden stuff, I thought it might be fun to look at the little other pieces of memorabilia that dot the museum, as well as some of its non-motorbike contents. For example, the small but wonderful collection of toy cars, both old and new.

Being half-Manx, I was also thrilled to see this vintage TT guide and assorted paraphernalia located in another section.

Nearby, you could even find one of the rarest of Mike Hailwood’s racing helmets from his four-wheel days, complete with matching shoes and gloves.

However, like I said, it’s not all automotive stuff here at the Iwashita Collection. The whole point of the museum is to build a sense of yesteryear before you get to the bikes and cars. Hence, the ground floor is all about early-mid 20th century products.

Like this old washing machine, complete with hand-crank wringer.

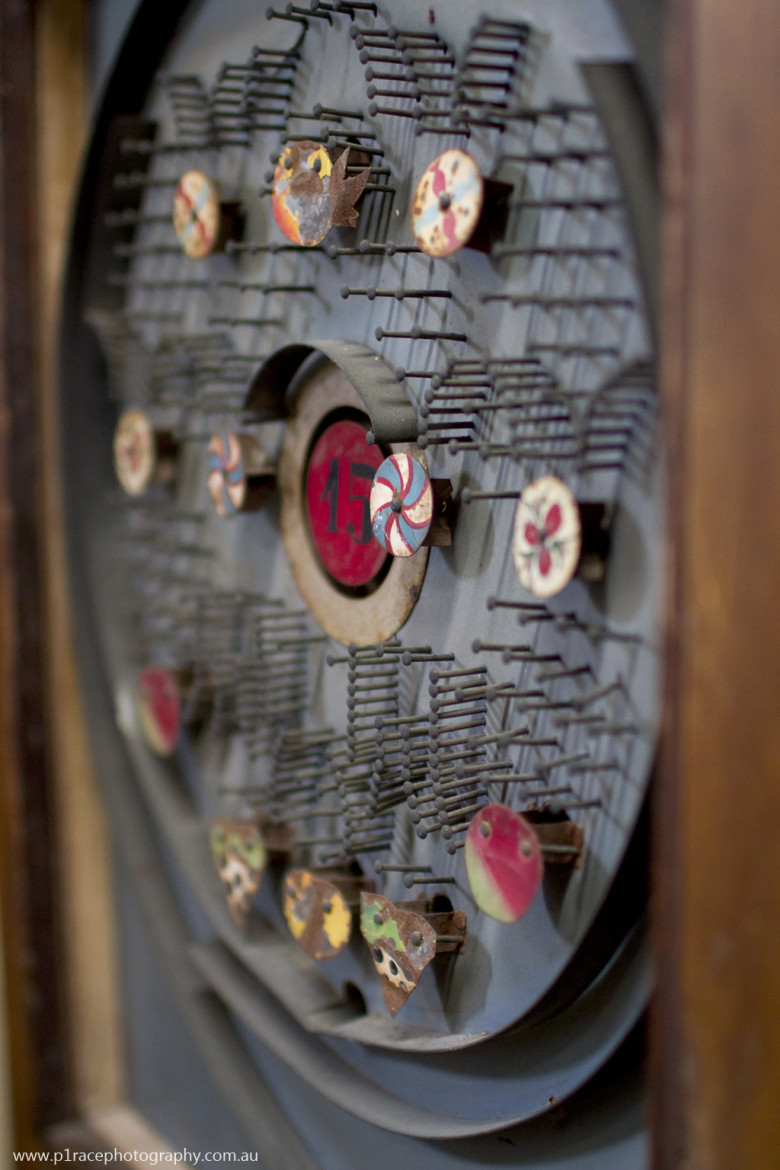

Or this very early pachinko machine, featuring decidedly hand-hammered guide nails. Not quite the LCD-screened, anime character-adorned, screaming money eaters of today.

You even had an F-86 Sabre fuselage nestled in the back of the building, sitting next to an old Buick-engined Formula car that I couldn’t identify. Amazing.

Eventually, though, we had to depart, leaving behind the shiny public museum building for locations slightly more… rustic.

And I do mean rustic. Hidden on a hillside a fair distance away from the main museum, and realistically in the middle of nowhere, lay the second of Mr. Iwashita’s three storage locations. We accessed it via a shed out the front, which was itself filled with wonders.

Such as this bubble car. Like almost everything in this location, this lovely little device was in decidedly bad shape, but Mr. Iwashita does plan to restore most of his collection eventually. He just has to finish collecting bikes first. Yup, unbelievably, he’s not done yet.

Another thing on the ‘to do’ list is this glorious ’59 Caddy, once owned by a famous Japanese pro wrestler.

Once you got into the main warehouse (no easy task, due to having to clamber over and under various items), you were greeting with this stunning sight. No, not Mr. Iwashita, seen in the background, but row upon row of almost completely unrestored Japanese classics. It was like walking into a tomb – low ceilinged and filled with skeletal remains, but all entirely precious. After banging my head several times on the roof beams, I quickly figured out I had to watch not just my head, but my back and sides too, making sure I didn’t knock anything over with my camera bag or second camera body.

Wherever you looked, the assault on the senses continued. Move to the right and you were greeted with another row of bikes and scooters.

Look behind, and yes, more bikes, along with some motorised bicycles. Older ones were on the right…

…while more modern ones were on the left.

Once I had got over the initial shock of the number and variety of bikes, and their conditions, I noticed that, while to some these bikes may look in ‘bad’ shape, there was a singular beauty to their dilapidated finishes, too. The dust softens the finish of the leather saddles, while the rust pockmarks the paint and metal with peculiar, yet somehow very natural patterns. It’s all very appealing.

I particularly liked the stippled and almost golden finish the years had given the paint around the Meguro logo here.

In some other cases, you ended up with an entirely different look; the rust making this bike’s black paint appear almost greasy.

However, with time pressing on, we had to leave, and drive half-an-hour or so to our final destination.

If you’re thinking this all looks a little factory-like, you’d be right. Mr. Iwashita made his money making car parts, and what was once a hive of machining and drilling is now the third of his storage locations.

As you can tell, the bikes here are in much better nick than in the other warehouse, with some actually being part of rotating displays at the main museum.

Thanks to their conditions, those that aren’t are also most likely to be cleaned up first and put on display.

That said, not everything here was just a spit-shine away from being put on show.

These Harley might need new tyres, for example.

I loved that, while Japanese bikes made up the majority, you could still find American and European brands here. I especially enjoyed seeing this hand-painted badge on an old Gilera. Simpler times.

As you would expect, I also received some history lessons. For instance, did you know Subaru made scooters? Well, technically parent company Fuji Heavy Industries, but yes. This one was called the Rabbit. Don’t laugh.

I also learned the origins of the famous Japanese bicycle brand Miyata. Turns out it didn’t always just make pushbikes…

By this point, my brain was already spinning from trying to take in what I had seen in the space of just a few hours. Then Mr. Iwashita told me there was an upstairs to this place, too.

Heading up past what used to be the old cafeteria, I climbed through a wooden window frame and onto a set of thin floorboards I was sure would collapse as soon as I set foot on them.

Thankfully they didn’t, and I pressed on to find what was arguably the most impressive part of the collection. It wasn’t that these bikes and scooters were any more historically significant than the rest, it was just the atmosphere. The perfect early afternoon sun filtering through the dirty perspex skylights, the seemingly higgledy-piggledy, yet, when looked upon from afar, perfectly arranged machinery. It was, despite the oppressive heat from being up in the roof, heaven.

The best part? There was a little bit of it left that I hadn’t discovered. Crossing a very precarious roof beam, I came across even more beauty. This stunning old Asahi had developed just the best patina from its years of natural entropy.

And looking back across the gap, you ended up with the perfect light on a trio of two-wheeled stunners. What a way to end a perfect day. This one will stay in the memory for a very, very long time.