They say if you’re really good at something, you don’t need to shout about it. And Historic and Vintage Restorations, or HVR, in Victoria, Australia, doesn’t need to shout.

Indeed, driving past, you wouldn’t even know it was there. There are no company logos visible on the building’s exterior – just leftovers from past occupants. The only thing that gives a hint as to what this company does is the interesting collection of cars in the forecourt.

That blue car on the left-hand side? That’s a JSR – a one-of-one prototype sports car made in Melbourne in 1951 in the Commonwealth Air Factory as a spare time project. Built with an eye to production by racer Ern Seeliger, it never made it off the ground due to costing double the average Holden price back then. The others you might be able to see? The red one’s obviously a Honda S600, while there’s a Morgan behind that and off to the right at the back lies one of several Lancia Aurelia coupes that comes in on a regular basis.

And that’s just the start of it. Walking in reveals a large workshop packed with the kind of metal that makes most car fans go weak at the knees. That Dino is a 246GT with the much sought after ‘chairs and flares’ upgrade package and is actually a barn find. The previous owner, having inherited it from her father, parked it for over 30 years after she drove it to the shops once, couldn’t find reverse, had to call roadside assistance to help her and was so embarrassed she never drove it again. The paint and interior are untouched, but all the mechanicals have been restored.

Behind that are the three Alfas, the brown GTV notable in that it is being turned into an Autodelta Montreal Alfetta, complete with genuine Montreal V8 engine. It’s one of several Montreal motors going into various cars in the next few months.

The white Duetto, on the other hand, is undergoing a full concourse-ready restoration.

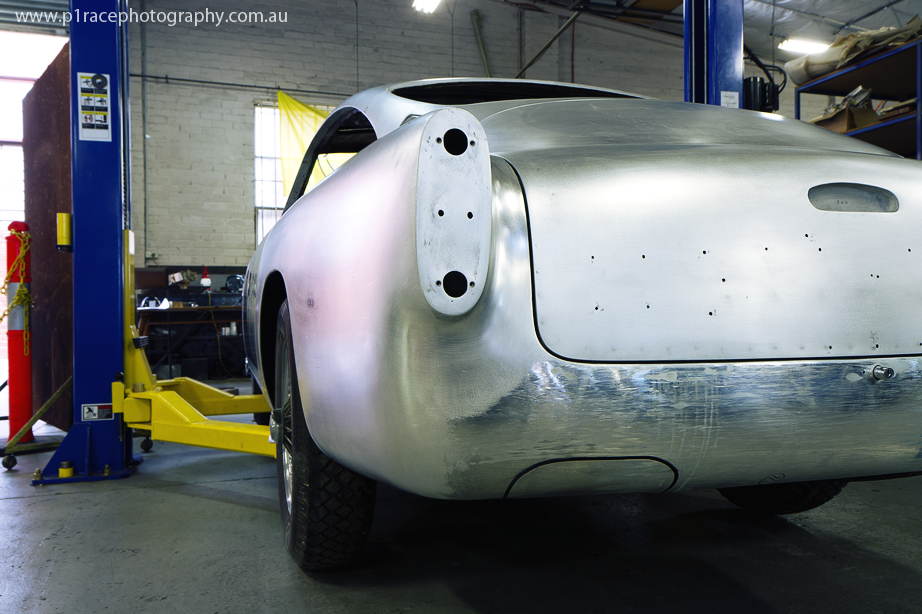

And of course at the back we have the DB4, which is a three-owner Series II that arrived from Hong Kong many years ago before eventually finding its way to Victoria via South Australia.

In for a full body and mechanical restoration, it’s actually in pretty good nick, given it originated in hot and humid HK, but there’s still a bit to be done.

As you can see.

One of the complications of doing such monocoque work, as opposed to body-on-frame jobs, is the need to widen the trolleys used to wheel the bodies around. Here you see the work actually being done, with body shop apprentice Nathan cutting the old work away in preparation for welding in wider beams.

As you can see from just the first few shots, HVR is serious business. And the machinery shown thus far is but a fraction of what’s spread out over seven completely different sections.

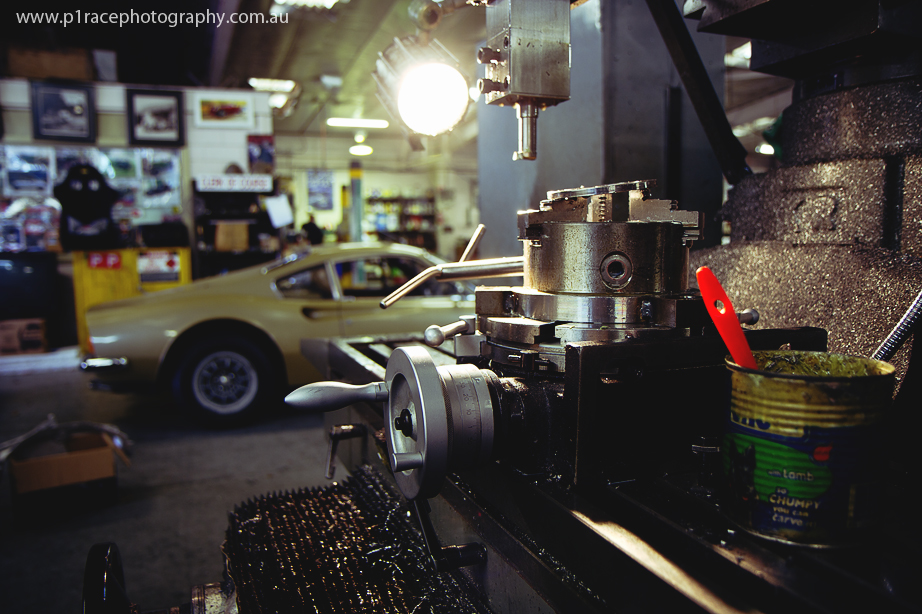

Off to the right-hand side as you walk in is the machining shop, where specialist Dave works his magic and produces everything from crankshafts to pistons to cams and gears.

While continuing to the right, you head out of the main workshop and into a storage area, which houses the overflow. Being HVR, this is no normal overflow, either. On the left lies a white George Reed Special Monoskate awaiting a race engine build (the owner has another one that was hidden under covers in the main shop, while his wife drives this one, and he also owns 32 Tudor hotrod you’ll see a bit more of later) while the 105 on the right also needed some love and attention, too.

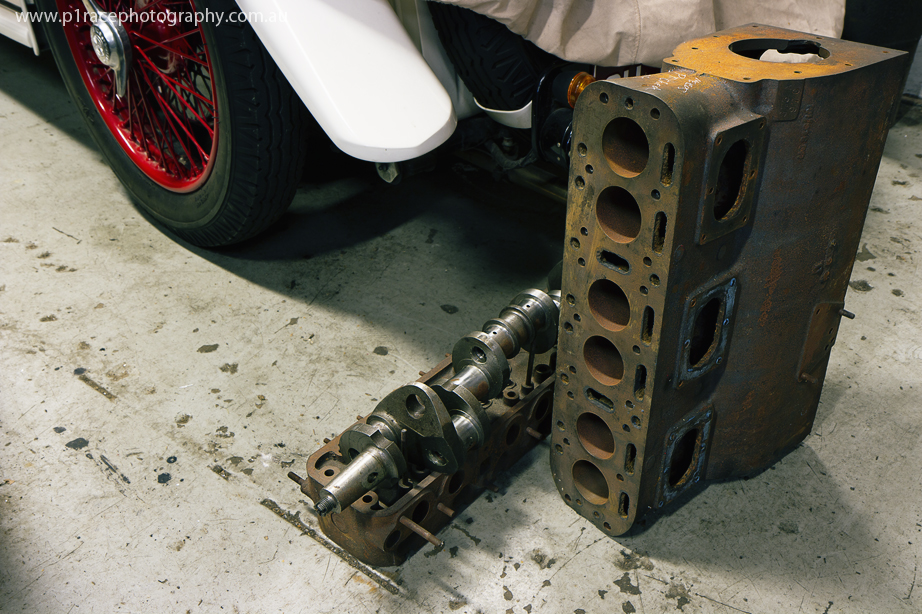

HVR owner Paul Chaleyer describes HVR as more of an ‘Italian’-style workshop than the clinical modernity of something like the McLaren Technical Centre, and in typically charming HVR fashion, the lack of space even in the overflow area meant a block and crankshaft lay just behind the green 105 and the car next to it – a beautiful MG L-Type with an 1100cc straight six (not the one laying on the ground, obviously).

Paul said this car had an extensive racing history, including competing at past Australian Grands Prix (back when it was based on a handicap system and small-engined cars could win) but had fallen into such disrepair that the owner basically handed HVR a pile of bits, not a working car. Yet there it stood, ready to ship to its new owner in New Zealand, another testament to HVR’s breadth and quality of work.

Next to the overflow car storage lay… you guessed it, parts storage. This is just one half of the main storage room, and there’s not much more than an inch spare anywhere. Exhausts, tyres, drum brakes, body panels, you name it, it’s here. It just comes with the territory if you’re about the only one-stop shop in the country that doesn’t specialise in one marque or model.

To be fair, not even HVR is truly a one-stop shop, though. It outsources paint, chrome plating, big sandblasting jobs and upholstery, but the rest it does in-house and is a testament to its skilled staff. That said, it does have a little paint booth for small jobs …

… as well as a sandblasting and cleaning room for those aforementioned small components.

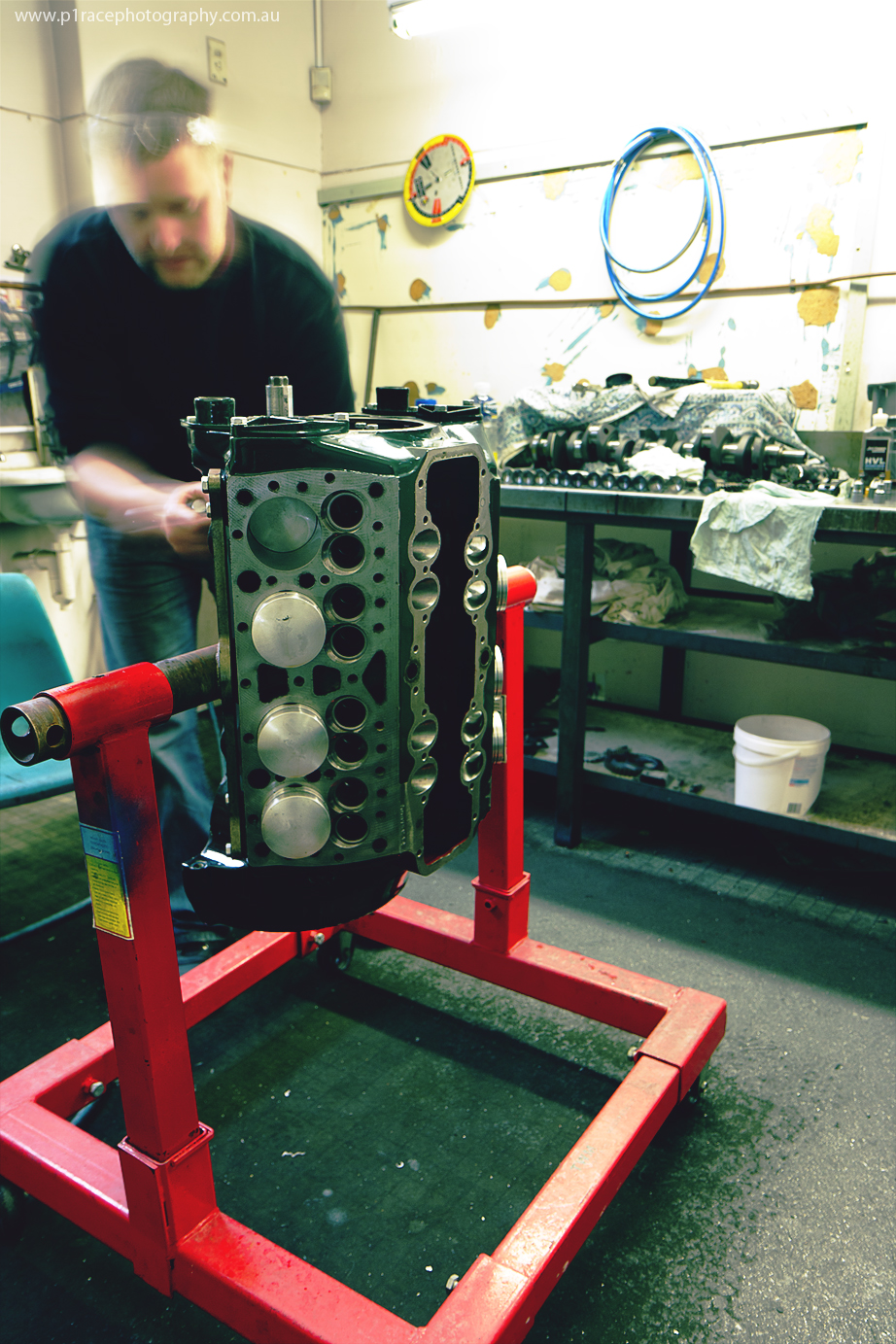

Passing back through the storage area, you come across the tiny little engine building room, where Chris (above, in a blur of movement) puts together some of the sweetest lumps you’ve ever come across. The day I visited he was working on the complete rebuild of the 32 Tudor V8, which looked to be coming together nicely, and indeed was apparently finished not long after I stopped by.

As anyone who builds engines for a living knows, though, it’s not as easy as it sounds. Chris estimates that he spends anywhere between 250 and 500 man hours per engine, depending on what needs doing and how many test builds are necessary. It’s seriously demanding work, and I admire his focus and dedication.

Returning to the main workshop, I came across some truly beautiful cars, including the aforementioned 32 Ford Tudor and an M45 Lagonda. The Lagonda was a fascinating car, mainly, as with all historics, due to its story. Owned by a friend of HVR boss Paul, it served as the driver’s university-era wheels over 50 years ago and, aside from a recent lay-off (hence the restoration), has been used ever since. Originally a sedan, it became a sports car 50 years ago after the original body failed to stand up to Australia’s ‘rugged’ roads back then. The best/worst part? It’s being sold after this because the owner’s kids find it too big and heavy.

Possibly the biggest surprise of the day, though, came in the form of this stunning 2.5 litre supercharged Riley Blue Streak. Hidden under covers at first, one of the shop’s apprentices, Henry, came to my aid and asked if I wanted to have a look. Obviously I agreed, and once revealed, I have to say I just gawped, completely floored by the beauty standing before me.

As you can see, it’s not finished yet, but it’s very close, and with the new financial year just begun here in Australia, the owner should be able to secure the finances needed to see it finished. Given it’s been a ten year project, I’m sure that will come as some relief. The colour? Riley blue, of course. Not that it was certain for a long time. Apparently things were such that, at one stage, Paul said to the owner that, “If you can’t make up your mind, you can paint it black – the non-colour”. Either way, I hope it looks just as good as this bare aluminium work does now.

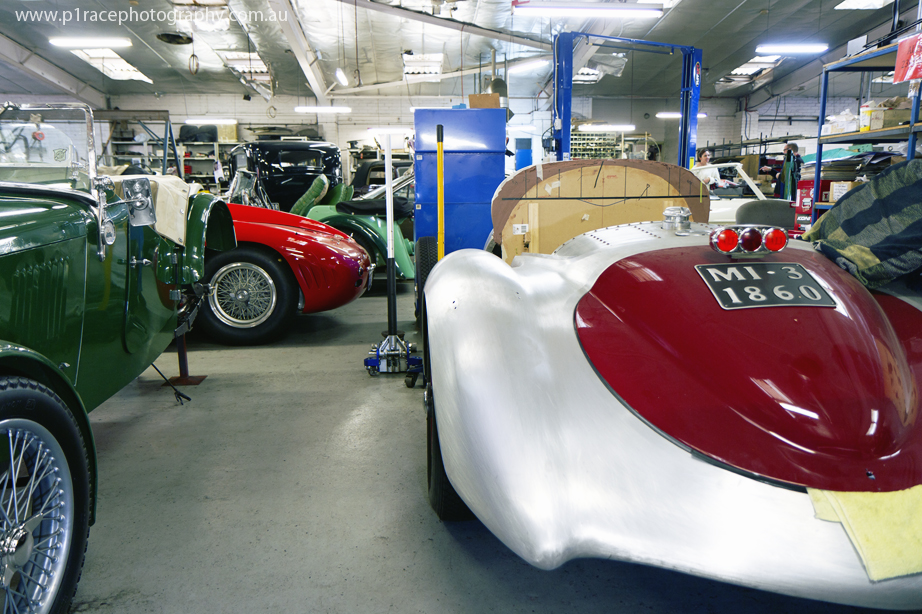

After I was done gawping, I moved across to the left-hand side of the main workshop, where the hits just kept coming. That green MG is a J2, just imported from the UK, while the red P-Type behind is an ex-Australian GP competitor, imported as one of only five or six by the then distributor, Lane’s Motor Cars.

Lane’s brought in the chassis and running gear and had bodies built by a company called Aspinal Brothers in the Melbourne suburb of Prahran – an area now known for trendy boutiques and youth culture. A locally-built steel body was necessary as the wooden ones from the mother country all fell apart when raced. As you can see, she’s a beauty.

Just behind those MGs lay one of the workbenches, seen here with various bits of propshaft and diff. I did say Italian-style workshop, right?

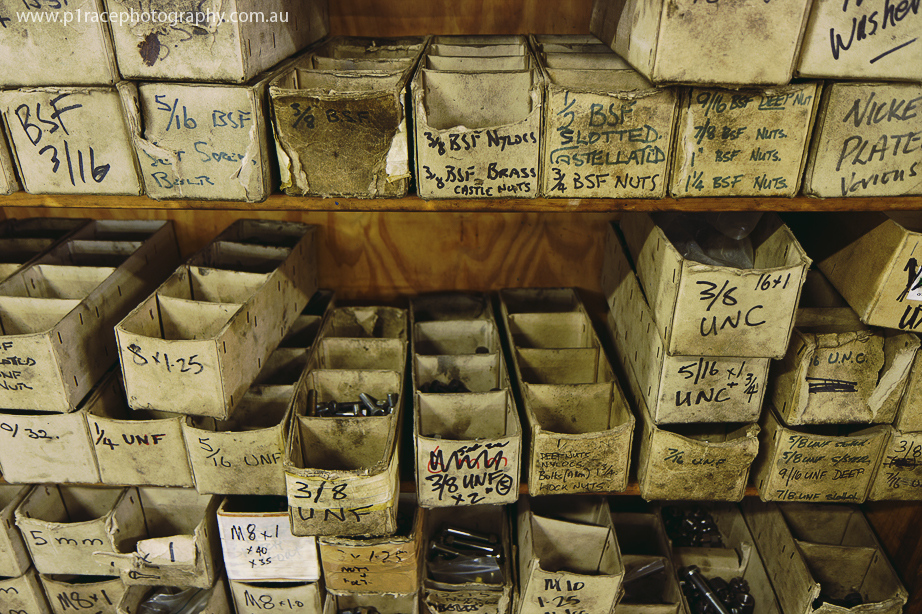

Of course, this doesn’t mean disorganisation is the rule, though. Everything is always carefully sorted out and things like nuts and bolts are kept in these wonderfully pantina’d cardboard boxes. After all, when you’re dealing with the number of parts these guys are, and when matching numbers can be a priority on certain builds, everything has to be right.

Next to the bench and hidden behind the two MG lay what is possibly the star car at HVR right now. A gorgeous Alfa Romeo 6C 2300MM (Mille Miglia) chassis with a specially-built gear-driven supercharged engine, the bodywork here is notable in that it was designed by Michael Simcoe in the Touring style to resemble the 8C 2900 Espada of Ralph Lauren fame. You may remember Mike’s name as the once head of GM design globally, but probably his most famous work is the V2 Holden Monaro, or the Pontiac GTO.

Now back in Australia after his time in the US, Mike was brought in to design the panels that give this Alfa its shape, and while my photos can hardly do it justice, thanks to its partially-painted panels and missing bits, this shoot, commissioned by the owner after the bare metal body was finished, shows you just how unbelievable it is.

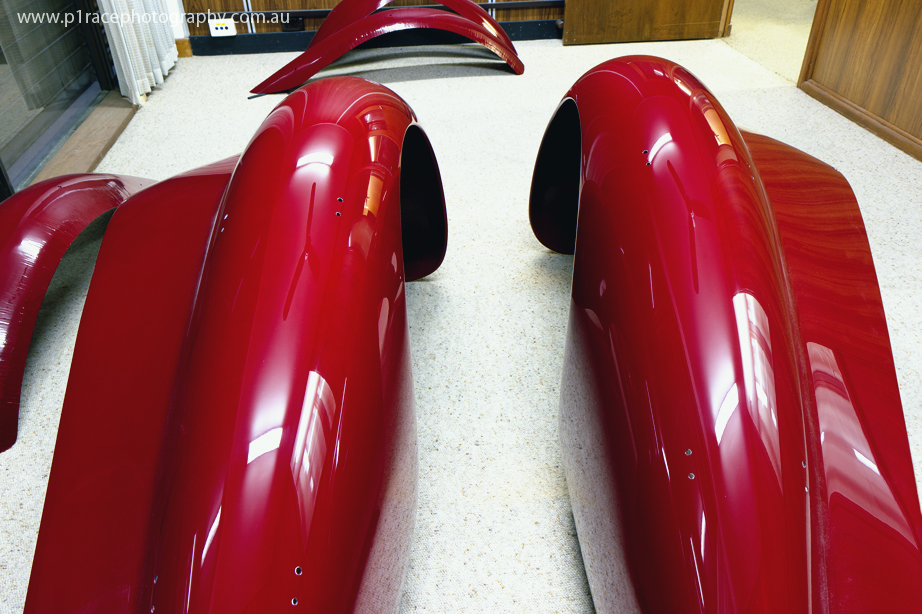

In a way, this is another car that, like the Riley Blue Streak, I wish would remain bare metal for the rest of its days, but as you can see, the painting process has begun, with only the rear cowl section ,which is one piece, awaiting its red coat. The rest of the body panels I will show you later, as they lie in yet another section of HVR’s cavernous workshop, ready to be fitted.

Now, the eagle-eyed among you might have spotted something rather sexy behind the MGs a few photos earlier. It’s something I also teased on the My Life @Speed Facebook feed a while back. I can now reveal it’s this utterly gorgeous Maserati 450S recreation.

I know, I can hear the purists’ groans from here. But when you look at how accurate the bodywork is, and how much effort went into getting the details right, you can acknowledge there’s a lot to be said for a piece like this, especially when countries like Australia tend to lack the multi-millionaire and billionaire car nuts other continents have who can afford the real thing.

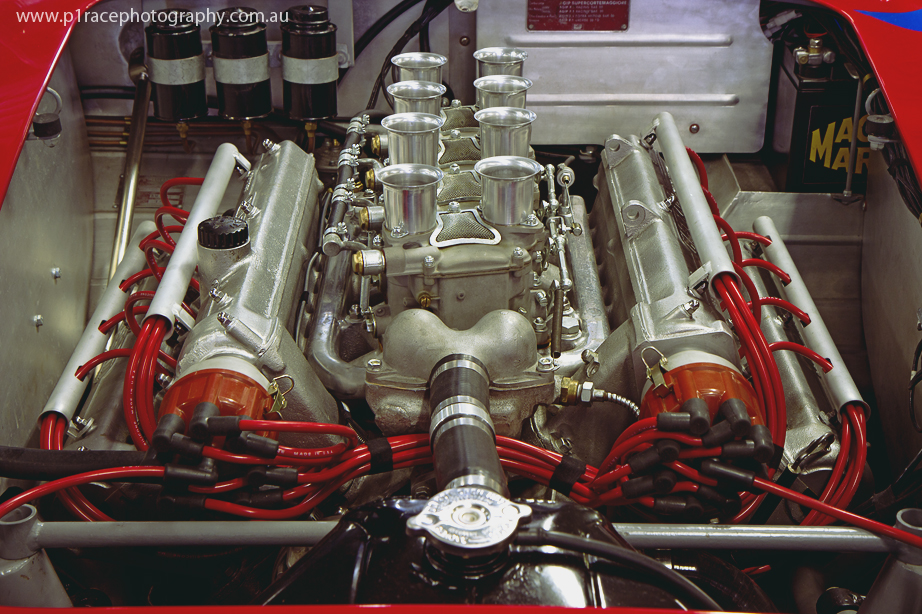

Indeed, according to Paul, there’s very little not realistic about this recreation. It has Boroni wheels, drum brakes, a DeDion back end and even a transaxle. The only part that’s not close to the real thing is the engine, sadly. And that’s purely because of cost.

“The problem with the Maserati is locating all the original parts, and we actually came across an original engine, but the price to buy the engine was almost [that of] the total build,” says Paul. So in the end, the owner settled on a 60s Quattroporte engine. Which, I’m sure you’ll agree, still looks nice.

The funny thing is the 450S recreation is just one of a large number of replica sports cars belonging to the one owner. Apparently, he also has a GT40 replica, three Shelby Cobra replicas (a skinny-wheeled Le Mans type, an FIA version and a 427), a D-Type replica, a 450 Testarossa built on a 250 chassis, a GTO built on a 330 chassis and others besides. And lest you think he’s just a replica hoarder, the owner also has several genuine Ferraris and Jaguars. “He has them all lined up and I think he just sits and looks at them. Looks at his ‘team'”, says Paul with a chuckle.

As for that gorgeous 1920s Salmson AL6 Sport GP above, it’s a complete restoration of what is thought to be an ex-Australian Grand Prix competitor, but apart from tracing its history back to Western Australia, and the fact the previous owner there (now in his 80s) remembers it as being “not a particularly memorable car”, much of its story has been lost and the owner is currently looking into its history to unlock some of its undoubtedly storied past.

Having explored the main building, I decided to head next door to the body shop, where I was soon to discover some of the most amazing sights at HVR, which is saying something. You see, here is where the magic that everyone can admire happens. Car fans may appreciate every piece of a car, but for most, the bits that make it move are hidden under the body. And the body is what makes the first impression.

![]()

And what an impression the HVR body shop makes. Filled at the time with two Alfas, one frog-eye (or bug-eye here in Australia) Sprite and a Lancia Beta, as well as the buck from HVR’s first incredible Alfa project – a 6c 2500 Competizione, also designed by Mike Simcoe – plus all the tools of the job, it’s a true insight in the craft of panel making.

Here, what starts out as a rusting hulk, like the Alfa above, can be cut, have new chassis sections prepared and welded in, and have new body panels beaten, polished and fitted, and be made ready for all the mechanical and interior bits to go in, all within one room.

Of course, some cars take more work than others. The Giulietta Sprint is at the point where one staff member (who shall remain nameless) joked that it might be easier to just cut the turret off and rebuild the whole bottom half from scratch. The amazing thing is that HVR could do that if they wanted to. Their apprentices and trained body builders are just that skilled.

What crept through my mind as I walked around in awe was a conversation I had with a race engineer friend of mine a few weeks beforehand. He said no one knew how to make anything anymore, and that some panel beaters didn’t even know how to use an English Wheel. I countered that places like HVR could (without having ever been there at the time), and lo and behold, on my first visit, I saw the evidence to back me up, along with an English Wheel and many other standard tools of the trade. Plenty I had no idea about prior to visiting, like the tree trunks used to help beat out shapes, and the leather sandbags used to refine things, but all were fascinating.

Big boss Paul readily admits HVR is lucky to have the apprentices it has, though, and that “retaining them’s going to be another thing … keeping them interested”. But he also believes that “the variety helps that – to know that every day something new comes through the front door and [brings] a new challenge”.

One of the more interesting challenges was the Lancia Beta. Not so much in that it was a particularly difficult job, although like all Lancias of the time, it needed rust cutting out, but in that its back story was quite amusing. Apparently, having heard Jeremy Clarkson describe the Beta as a truly terrible product, the current owner of the one on the rotisserie decided to restore it, document the process, then drive around Australia and document that, finally sending the tape into the BBC as evidence. I look forward to seeing the result.

The final part of my journey through HVR came when I headed up a flight of dark and slightly terrifying stairs to a floor above the main workshop. Here, I could see the final, painted panels for the Mike Simcoe 6C. The landscape here was very much of the 70s, complete with brown everything and panelled-off separate offices. But amongst the awful decor lay the beautiful painted panels of the 6C. Seriously, just look at those curves.

Suitably blown away, I headed back downstairs to interview Paul (seen below with daughter Dominique, who races a 105 she calls Big Red in her spare time) and reflect on what had been a glorious day spent among some of the most unique and beautiful cars of all time. HVR really is a wonder; a rare national treasure only matched in coach-building and repair skill by the very best in Europe and the UK. If you’re ever in Melbourne, I highly recommend dropping in for a look. Just be sure to keep an eye out for the eye candy out front. Otherwise you might miss it and drive right by.