I’m pretty certain very few people lie awake at night, thinking of what new engine they’d like for their car. Most just think about the car. And this is to be expected. After all, the engine is an integral part of the car. But its integral nature also means the beating heart of the machine is also sadly neglected when it comes to museums. We celebrate the car and the bits inside, but we rarely celebrate the heart by itself.

Thankfully, Nissan thinks differently. It recognises that these amazing pieces of engineering deserve some recognition of their own. So it set up a museum just for engines in the old Nissan factory headquarters in Yokohama’s harbour-side industrial hub.

From the outside, it’s nothing special. Pre-war Japanese factory architecture is hardly a celebrated area, and for good reason. But within this slightly depressing concrete block lies some of the wonders of the machine age.

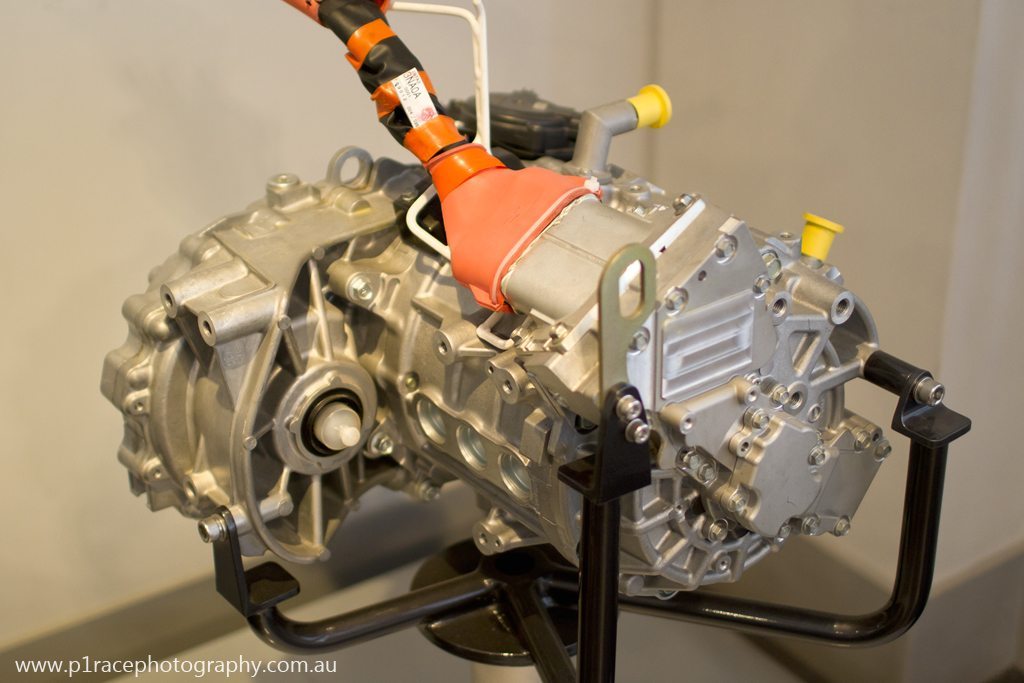

It starts off, rather oddly for a museum, with a very contemporary exhibit – Nissan’s current engines. The first of which you see is the motor from the Leaf. It’s amazing to think that such a compact piece of engineering, and its successors, is what will likely drive our future commuter (and eventually even our racing) cars. But Nissan has bet the farm on electrics, so it’s perhaps apt that you start your journey into the past via what may well be the future.

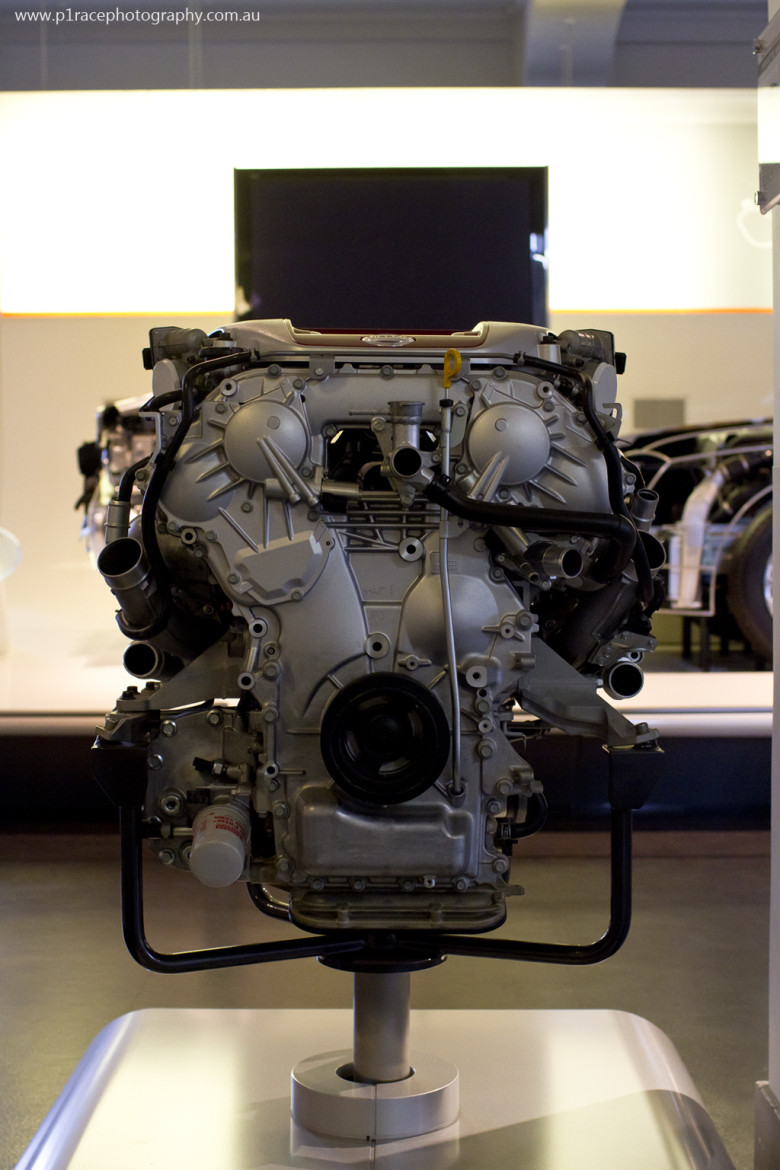

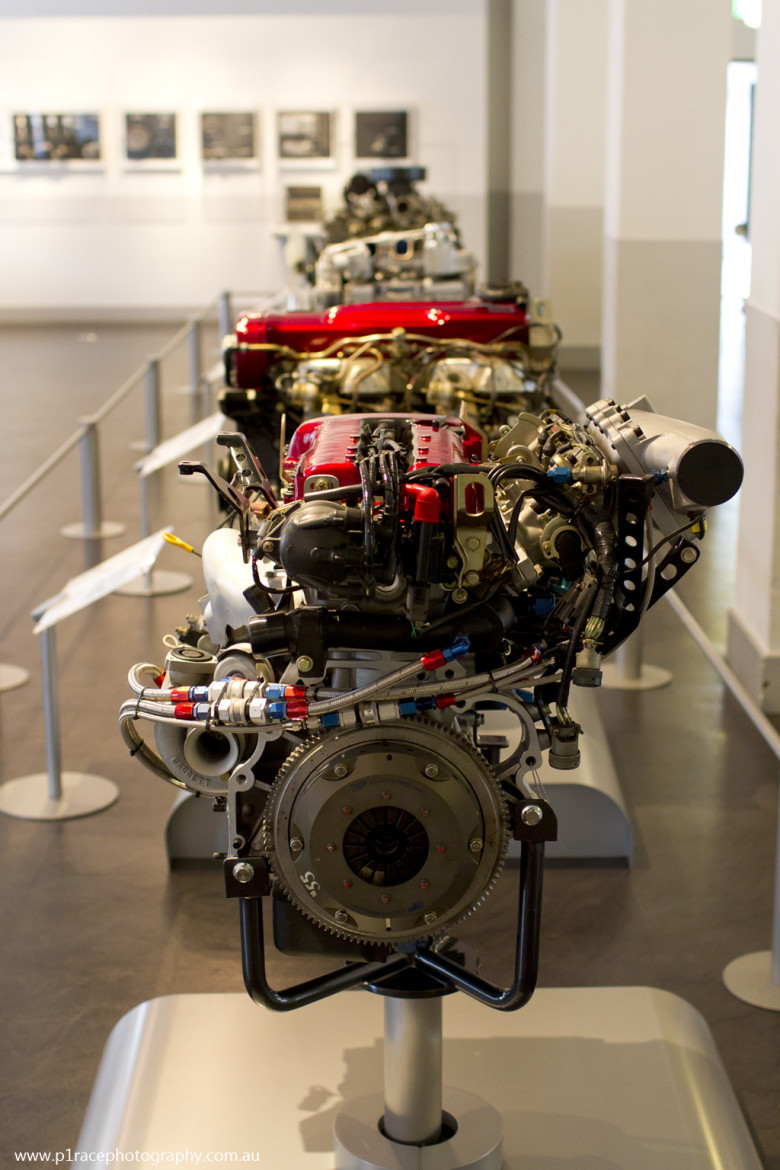

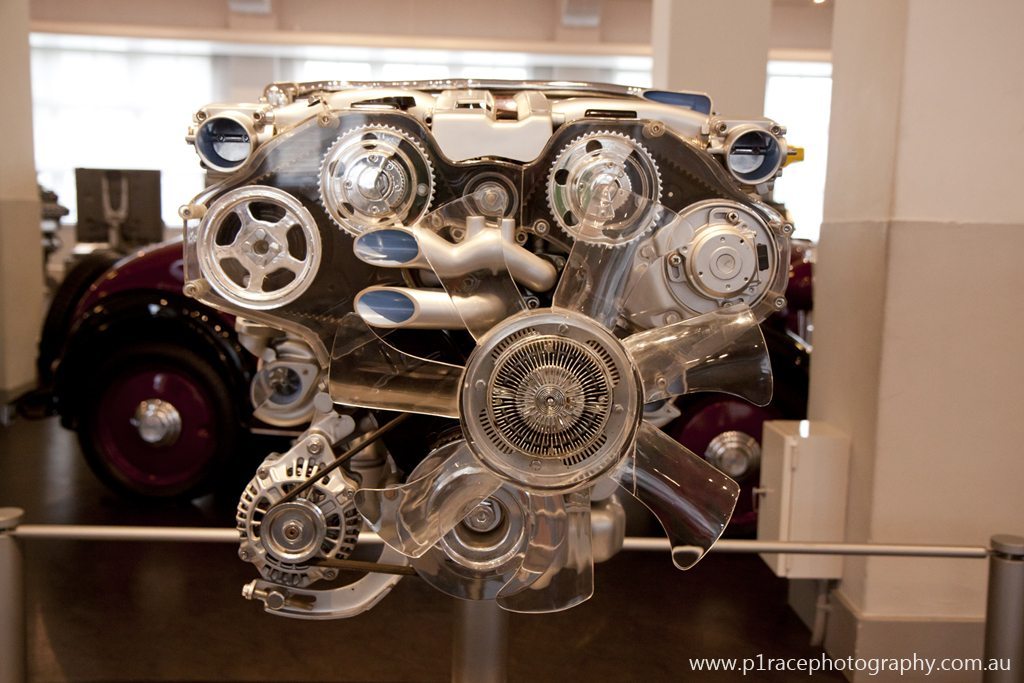

Of course, My Life at Speed-ers are probably more interested in what you encounter only a few steps away – the heart of Godzilla. It’s only when you look at this motor in isolation that you see what an impressive feat of engineering it is. Sure, it’s not a former racing engine, but it still puts out 800hp with comparative ease and has continued the GT-R legacy well.

Sitting behind the VR38DETT is an example of one of Nissan’s less sporty models – the last-of-the-line Gloria, complete with cutaway body sections and an example of its engine out front. While hardly the zenith of anything Nissan did, it’s still fascinating to see what goes into these cars and the usually hidden internal workings.

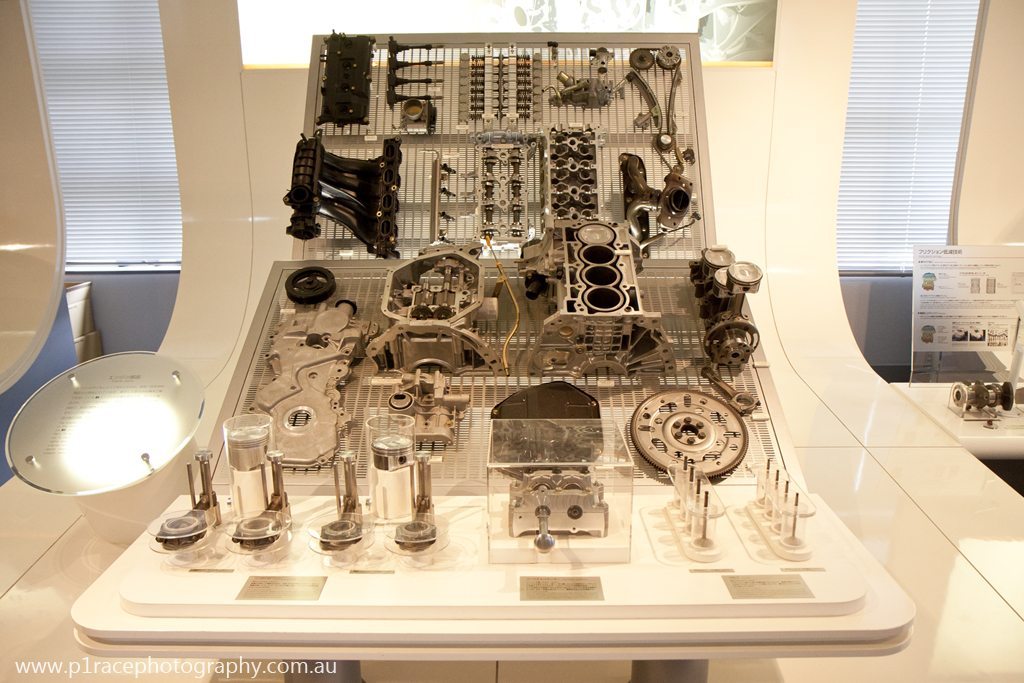

Speaking of which, if you really want to geek out, there’s a fully exploded view of one of Nissan’s current four cylinders just to the left of the Gloria exhibit. Legendary sports engine it may not be, but I defy any car-nut not to be fascinated by this great look into the guts of a modern engine.

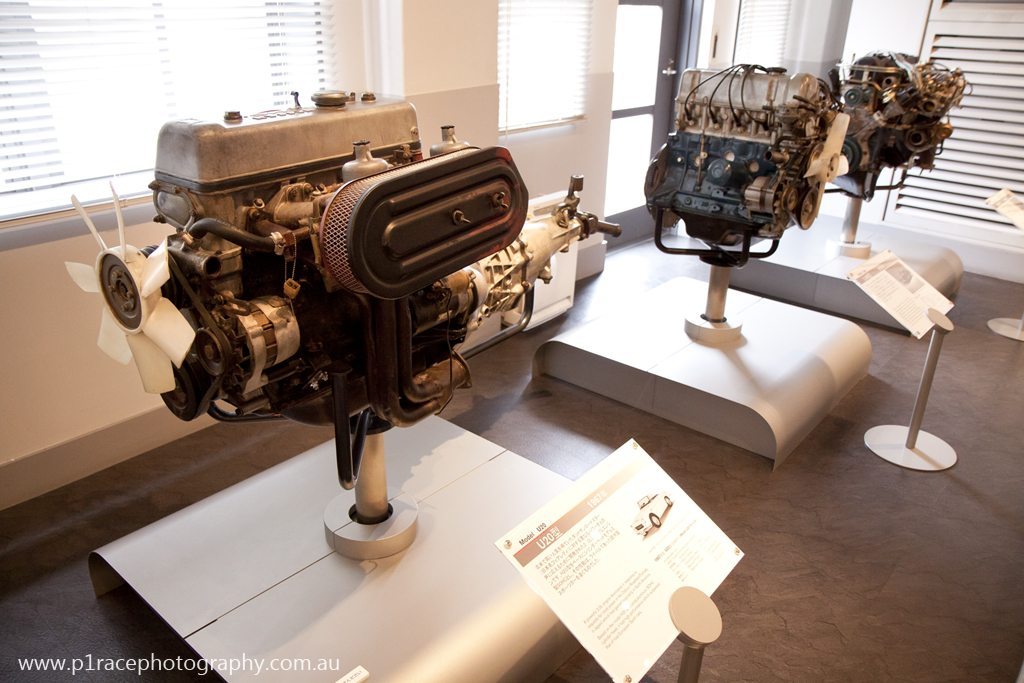

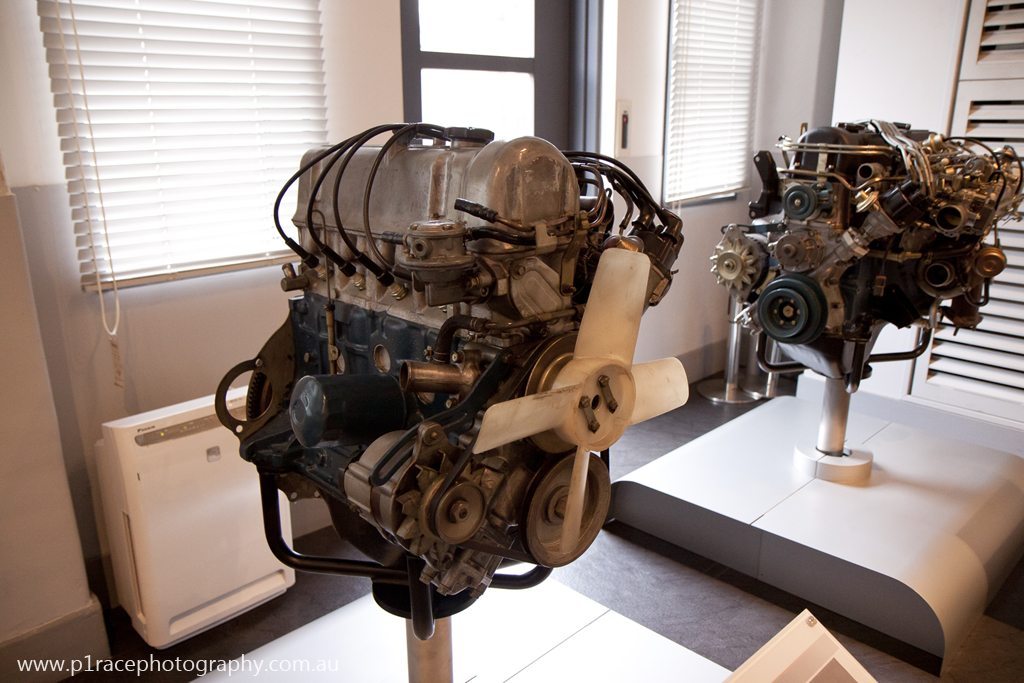

Having covered much of the modern Nissan line, you eventually walk through a wide-open doorway into what I can only describe as the hall of kings. Split into two halves, on the left-hand side of the first half is a line-up of many of Nissan’s earliest and most influential power plants, including the NC truck and Patrol engine in the foreground, and the fuel-efficient A10 four cylinder and G7 straight six from the earliest Prince Gloria (and later Skyline GT) further down.

One the right, though, is what will probably get most readers drooling – examples of the Hakosuka’s S20, the VG30DETT from the 300ZX, the RB26DETT and the SR20DET. The eagle-eyed will have spotted the SR is not your usual example, either. In fact, this is from an old GTiR rally car, hence the upgraded bits and pieces.

Looking back at the earlier motors, it’s clear to see Nissan’s origins and also just how long a single design can last. The A-series OHV four cylinder, for example, was based on an improved BMC design Nissan started selling in the late 60s (remember Nissan was an Austin licensee), and is still sold today, albeit in a much modified form.

Others may not have lasted so long, but were equally significant. The U20, of course, powered the Fairlady SR311…

…while the L18S above is one of a storied line of motors, running from the four cylinder versions in the Datsun 510, to the later six-cylinder variants that made their way into the 240Z and others.

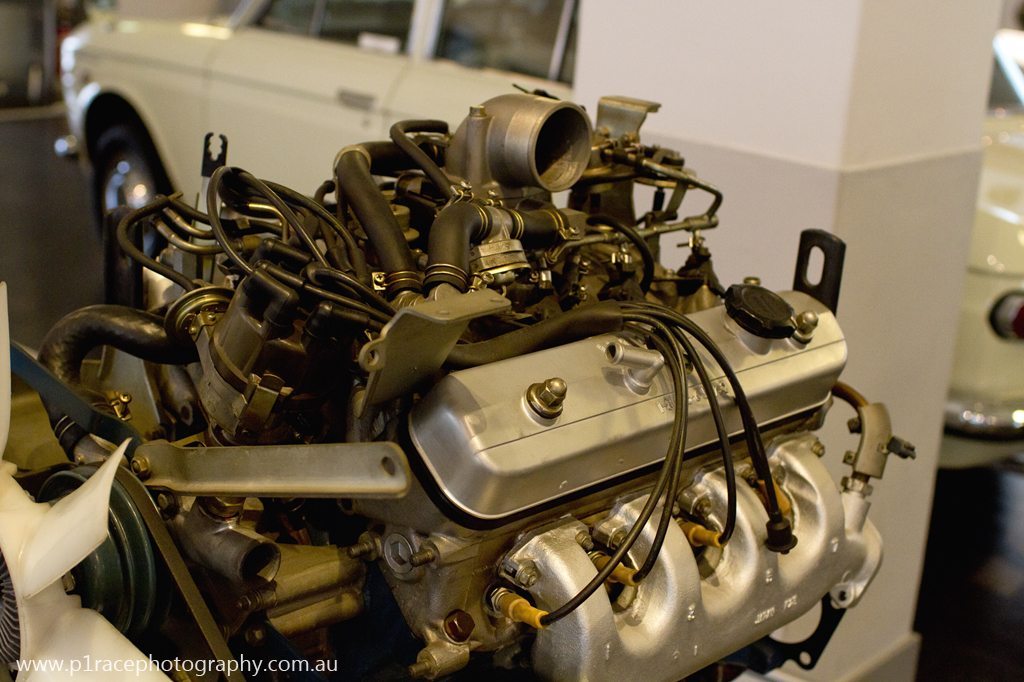

What came as a surprise was how Nissan did not include any examples of the L20 itself. Instead, they chose what was possibly a more significant engine in the L20 ET – Japan’s first ever passenger car turbo engine. Easily recognisable as a descendent of the Z engines, the L20 ET packed 145hp from its two litres and in true late 70’s/early 80’s fashion, made very sure everyone knew it packed a turbo punch.

Moving around to side with the RB and SR20, the line-up actually starts with one of the rarest and most unusual of Nissan’s motors – the Prince W64.

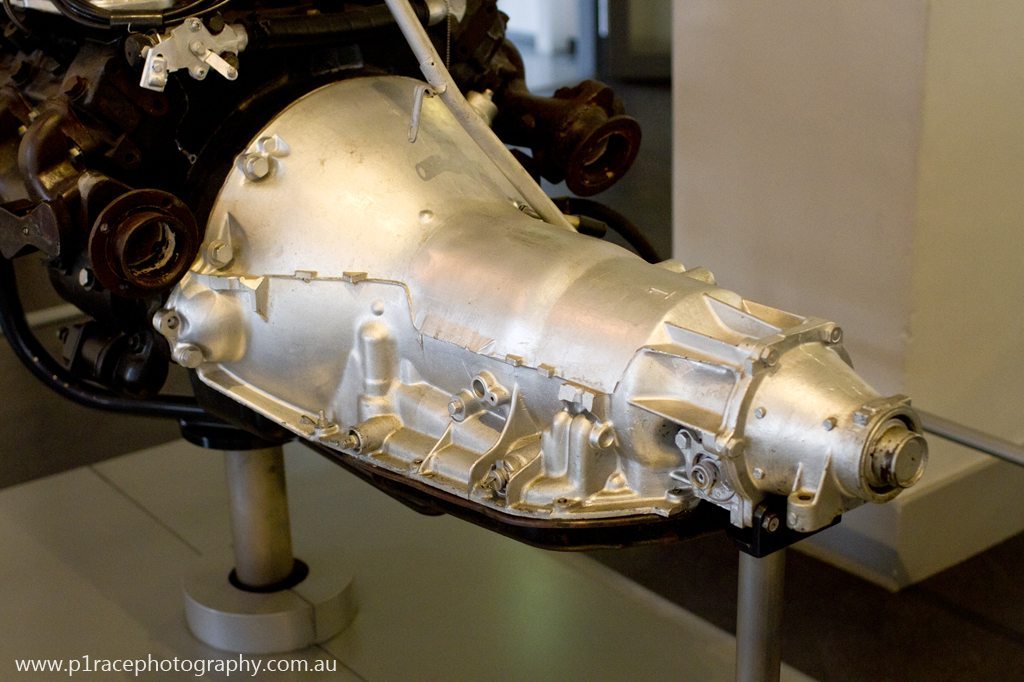

One of only eight built to ferry around the Japanese royal family, the W64 is notable for several things, not least of which is its enormous alternator. According to museum curator Hiromasa Maeda, this curious piece of design was due to the peculiar requirements of the royal family – namely that they travel in a very heavy luxury sedan (the Prince Royal limousine) at very low speeds. A smaller alternator would apparently not have kept the car going.

Another unusual aspect of the W64 is the decidedly un-regal exhaust manifold welds. Apparently this quick fix came about as it was not economically viable to cast new ones when the existing headers cracked. I suppose when you only have eight engines, it makes sense to patch them up, rather than start afresh.

Upon closer inspection of the W64, the shape under the custom casting indicates the presence of a very American GM auto ‘box.’ While Nissan could build the engine, it did not have the resources to design and build a custom automatic for their limited-run V8, so had to rely on US expertise to get the job done.

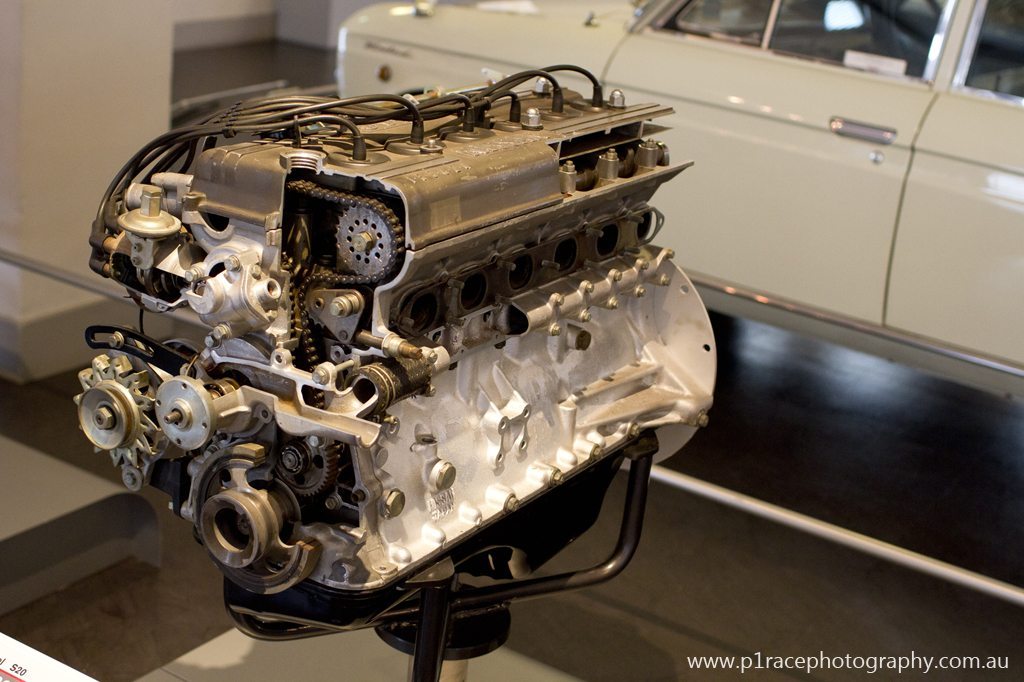

Next to the W64 lay an engine that should need no introduction. I have to say, I felt sad they had cut into this one, though. Education is a fine thing, but did it have to be this engine that paid the price?

Oh well, at least you can see the inner workings, as well as little details like the firing order cast into the cam covers.

After the S20, this next engine came as a little bit of a letdown, but it is very important, being one of Nissan’s earliest first mass-produced V8’s, the Y44. Based on the Y40, Nissan’s first ever passenger car V8, the Y44 shown here gained electronic fuel injection and a three-way catalyst to meet emissions regs of the time, and the President model it came with was also notable for having Japan’s first optional anti-lock braking system.

Before we get to the two most legendary modern Nissan road car engines, I thought I might include a shot of the 300ZX’s VG30DET. Much maligned over the years for its unresponsiveness to tuning and general unreliability when modified; it’s still significant for powering what many in the West saw as Japan’s first serious modern sports car, one that won awards in North America for years after its release.

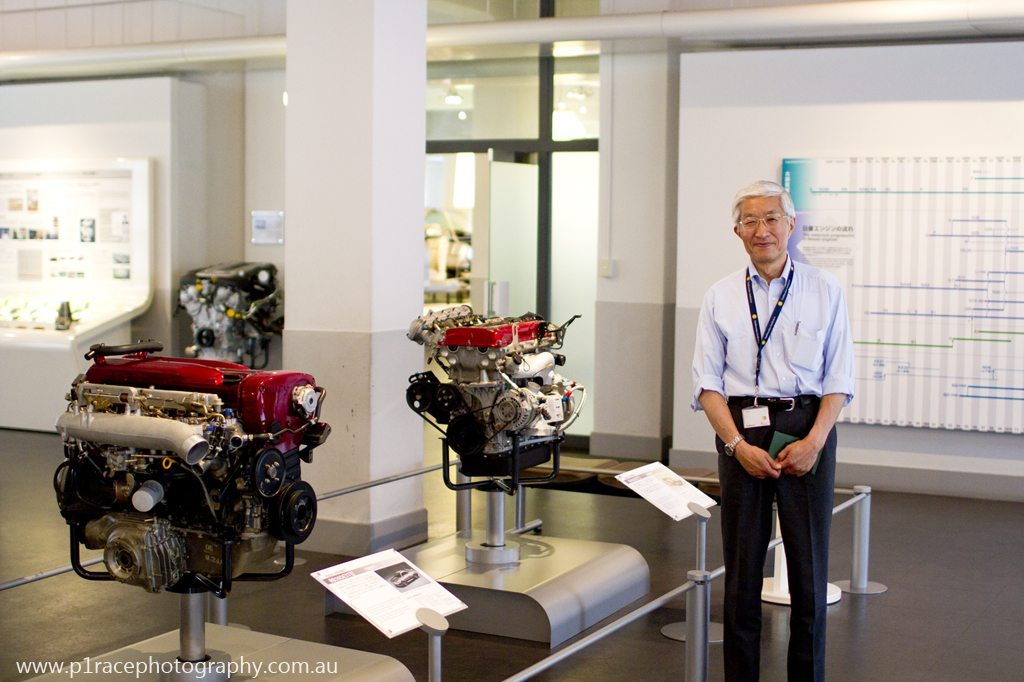

Ah yes, the RB26DETT and SR20DET. What can be said about these that haven’t been said before? Very little, which is why I think it’s about now that I should formally introduce the Nissan Engine Museum’s curator – Hiromasa Maeda. Those who follow Japanese car history closely may already know of him, but for those who don’t, this is the man who led the design team for the SR20 and designed the turbo system on the RB26DETT himself. He’s a bit of a legend, obviously, and the perfect man to lead you around the museum, knowing, as he does, more than most about these power plants.

It’s from him I learned the stories about the W64, as well as many other anecdotes, but huge knowledge base aside, I think the best part of meeting Maeda-san was finding out just how wonderfully humble and education-focused he was. The car world is filled with enormous egos, but despite his history, Maeda-san downplayed everything he did, and took true pride only in his role in educating others. I wish more people were like him.

Moving around to the other side of the main hall, you encounter these two beautiful examples of Nissan’s four-wheeled history. The Bluebird 1300SS in the first image is famous for being the first Japanese car to win its class in the East Africa Safari Rally in 1966, while the Datsun Type 15 Roadster, while not as significant, is probably one of only a few restored to this level.

What you might have noticed in the background of the two cars is some of what lies on the other side of the hall of kings – Nissan’s race engines.

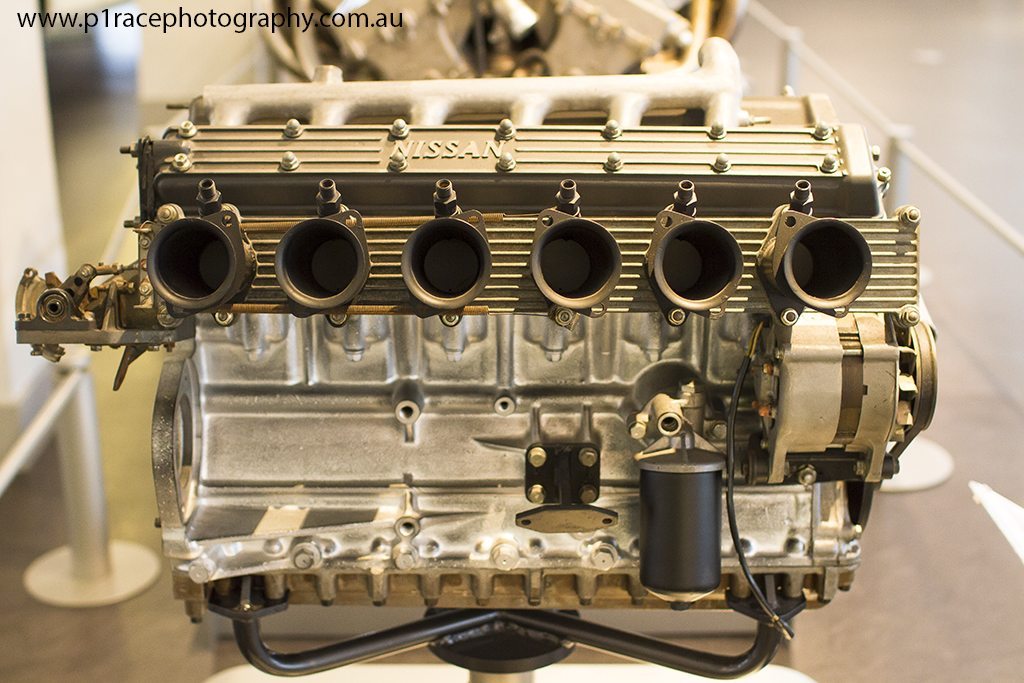

Starting with the incredibly beautiful GR8 straight six, you could see examples of each significant sports car motor.

That included one of Japan’s most important engines full-stop, the GRX-II from the R382. Notable for winning the 1969 Japanese GP (beating Porsche 917Ks in the process), Japan’s most powerful engine of the time, and its first V12, still inspires awe.

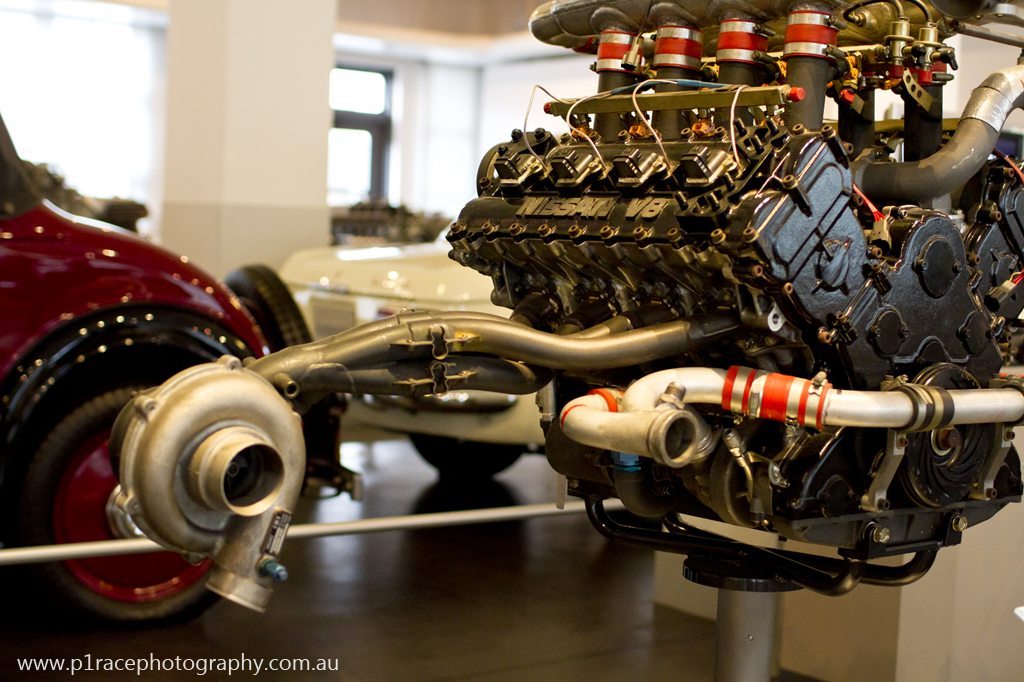

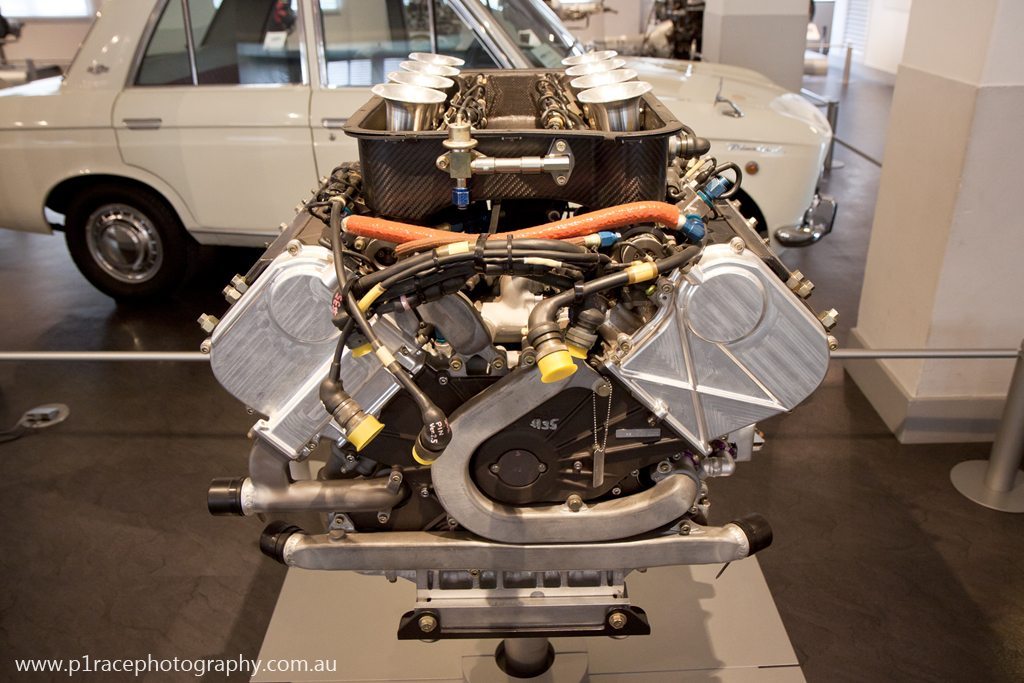

As does the next engine in the line-up, the VRH35Z, used in the R91CP, this turbo monster turned out well over 680hp (it was actually reputed to put out closer to 800) and ended up winning the Daytona 24hrs in 1991. The far-out turbo location was due to the design of Group C cars, which placed the radiators/intercoolers in the side pods, and necessitated the turbos being placed near them. Maeda-san said it didn’t actually affect response much, which came as a surprise.

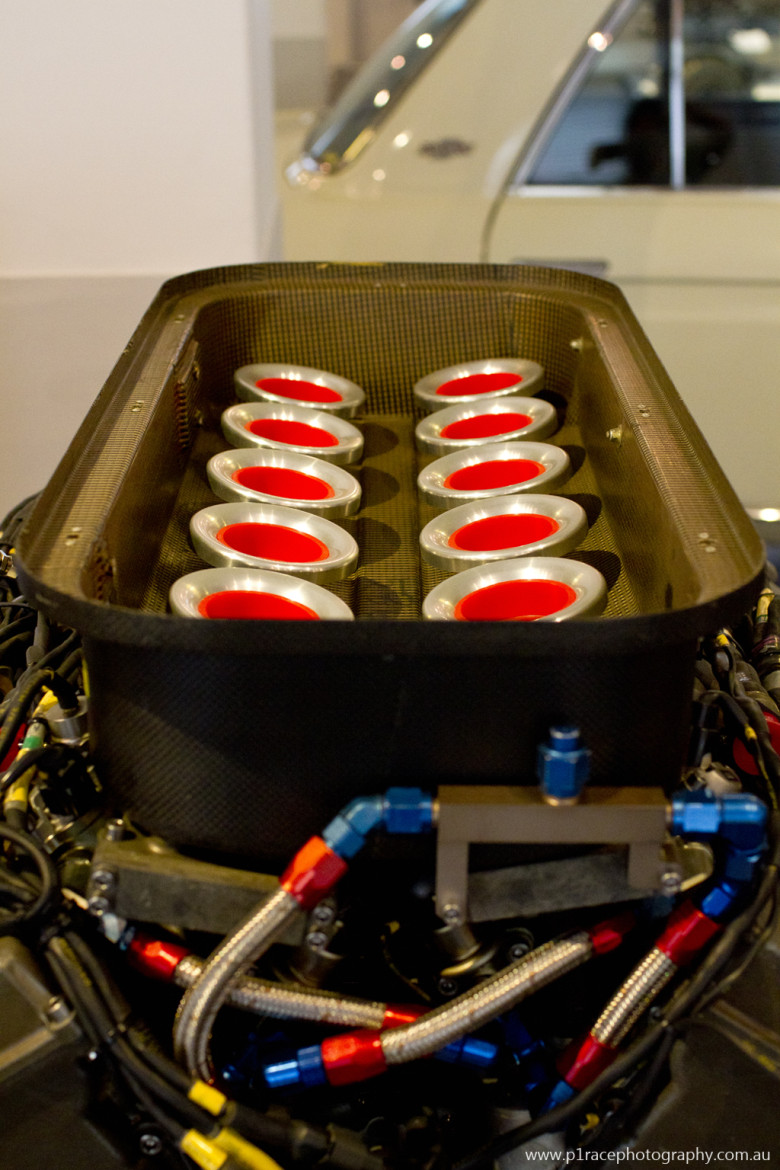

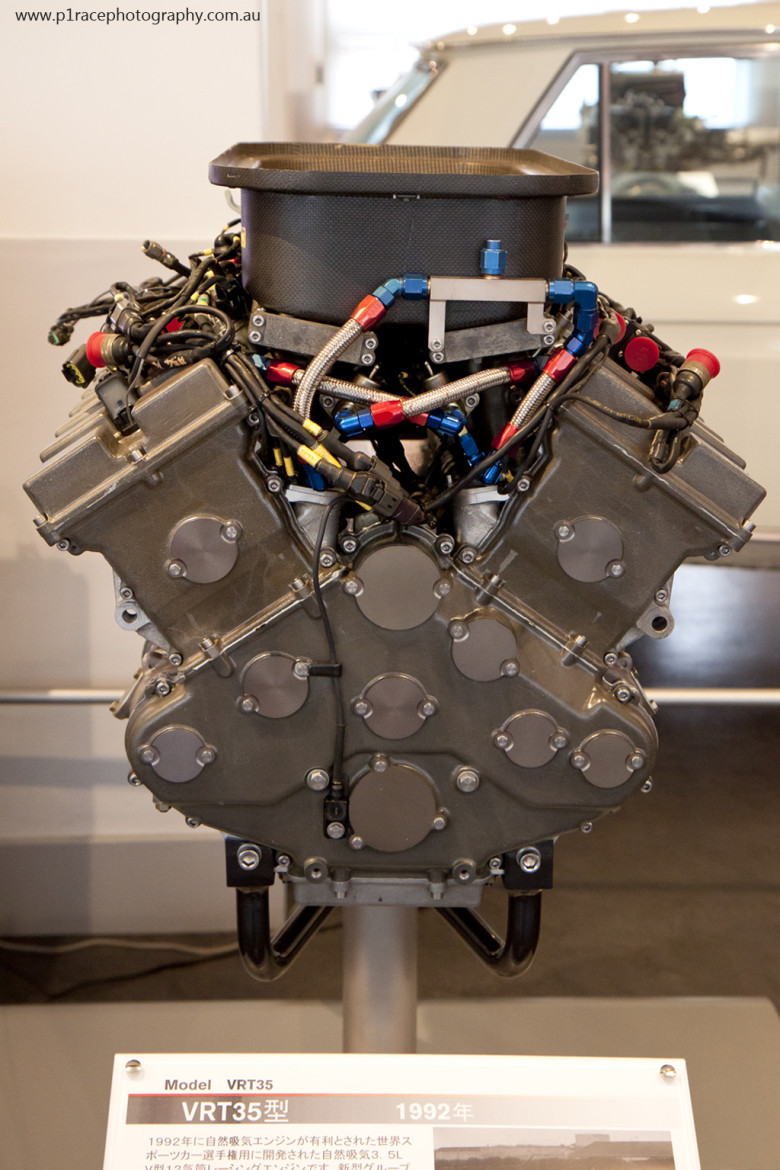

If you want true response, there’s nothing like a naturally-aspirated motor though, and indeed, there has never been much like the VRT35 before or since. Designed for Group C in 1991, but only used in one race before Nissan’s circumstances dictated a change of plans, the VRT35 produced 630hp at 11,600rpm and apparently sounded like nothing else on earth. I wish there was a video somewhere, but a quick Google search yielded nothing. Oh well. Hope you enjoy the photo below.

Finally, we get a more recent Nissan V8 – the 1999 VRH50A. Famous for winning the Fuji 1000, it’s a bit of a curio, in that it while it won a major endurance race, it never had the chance to be successful after that, as Nissan cut its prototype program in 2000, during the initial years of the Ghosn consolidation. Still, nice to see it has a place in history here.

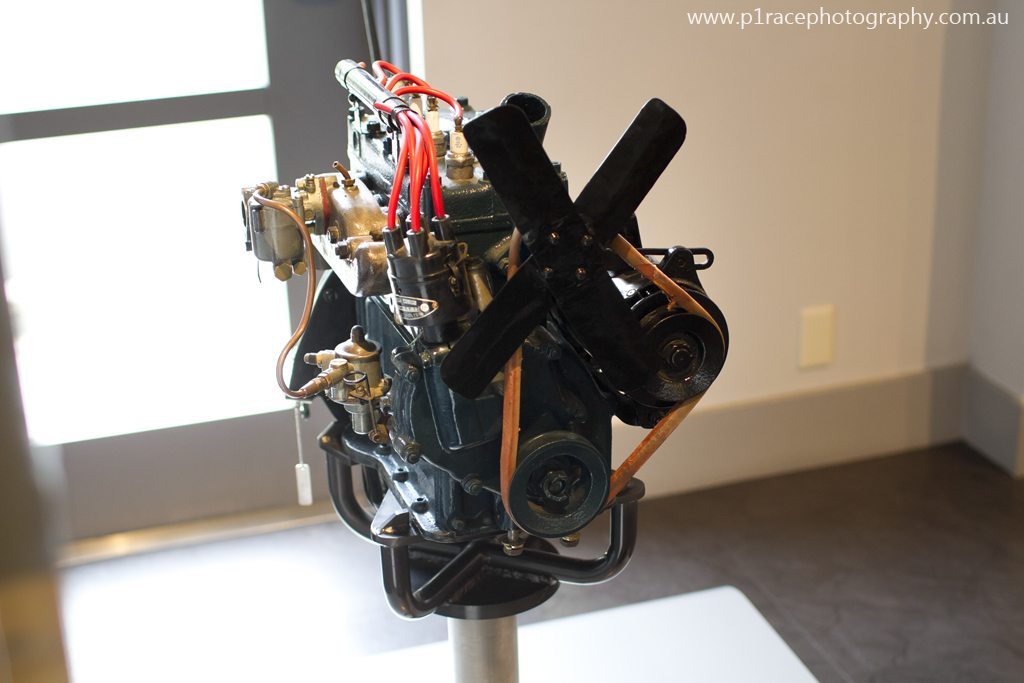

Before we finish up downstairs, I could not leave without showing you Datsun’s first ever engine – the Type 7.

Hidden away in a corner opposite the race engines, the Type 7 powered the beautiful 1935 Type 14 Roadster (although with only 15hp, powered is a relative term) and as mentioned, was the first to carry the Datsun name, as all prior engines had been badged DAT, after the surname initials of the three founding investors in the company. It remains a milestone of the company’s engine production expertise and a gorgeous little piece of work.

Guided by Maeda-san up the stairs, we emerge in a corridor with two large rooms on either side, ones which I later found out were executive offices in days long past. In the first one, I discover a display explaining Nissan’s full history in Yokohama, which not only gives an explanation of the company but also the city to which it is tied.

It also features one of the best model car collections I’ve seen. Every major Nissan car is on show, although rather predictably, I focused on the sports models.

Of course, you had all the various Z models on display…

As well as Fairladys, seen here in the background…

… and of course Skylines.

Lots…

…and lots…

…of Skylines.

Did I mention there were Skylines?

In all seriousness, though, given how important the Skyline name has been to Nissan over the years, it’s only appropriate they fill their model car collection with them. Being an Aussie, I was happy to find an example of the Jim Richards/Mark Skaife 1991 Bathurst 1000-winning machine, too.

Having seen the engine for the real thing downstairs, I enjoyed also seeing a model R380 upstairs.

Not to mention miniature examples of Nissan’s other tin-top racing cars. Note the Mazda models on the left – Nissan, like other Japanese manufacturers, is excellent in acknowledging competitors over the years.

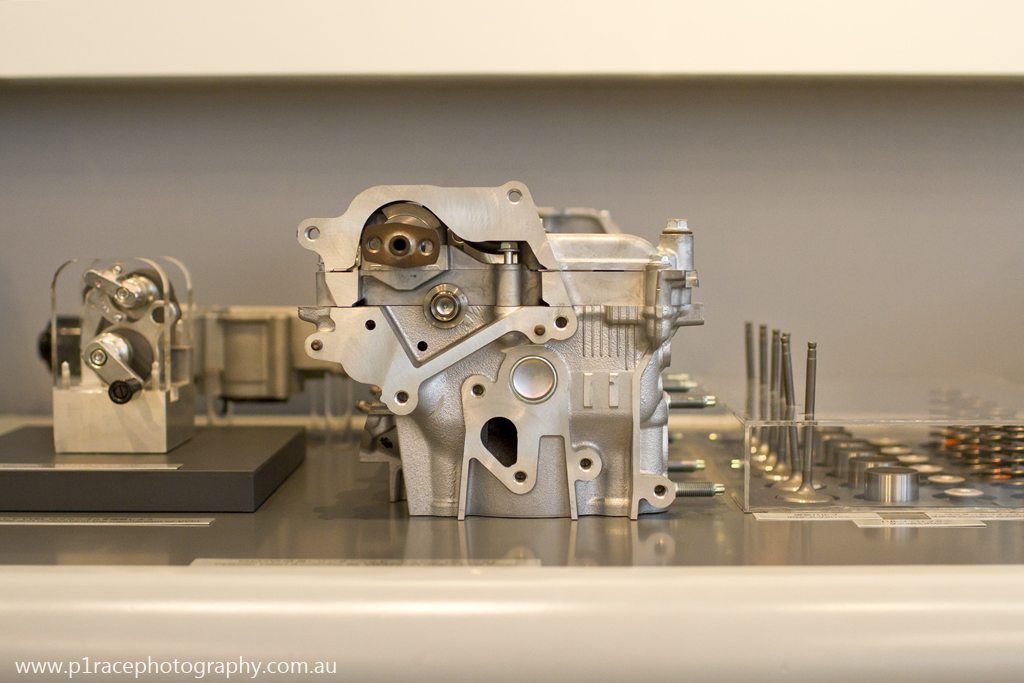

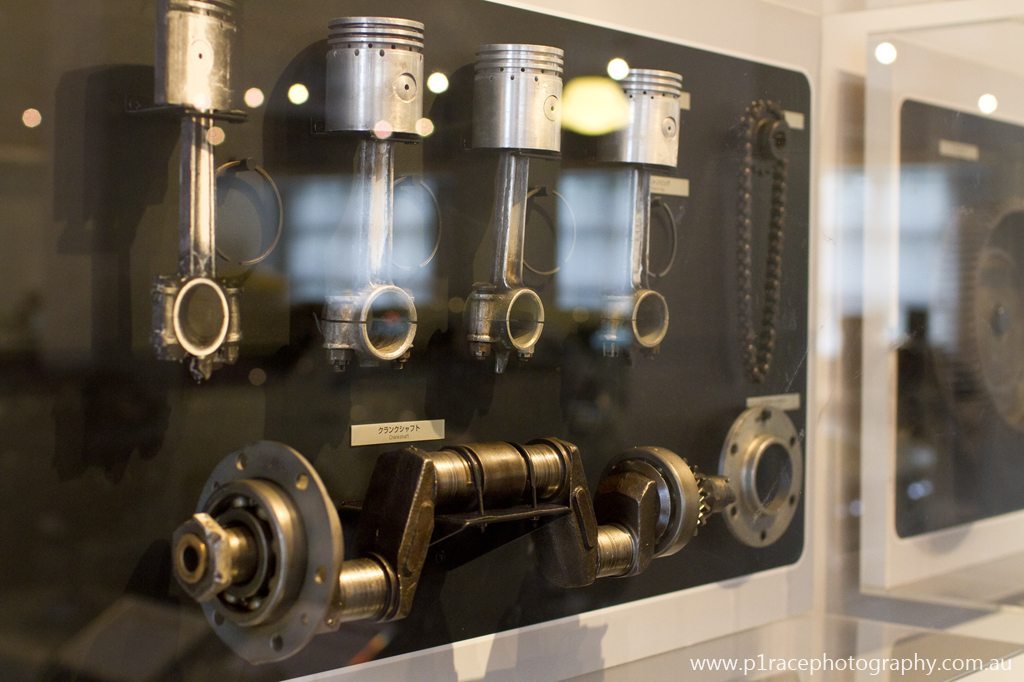

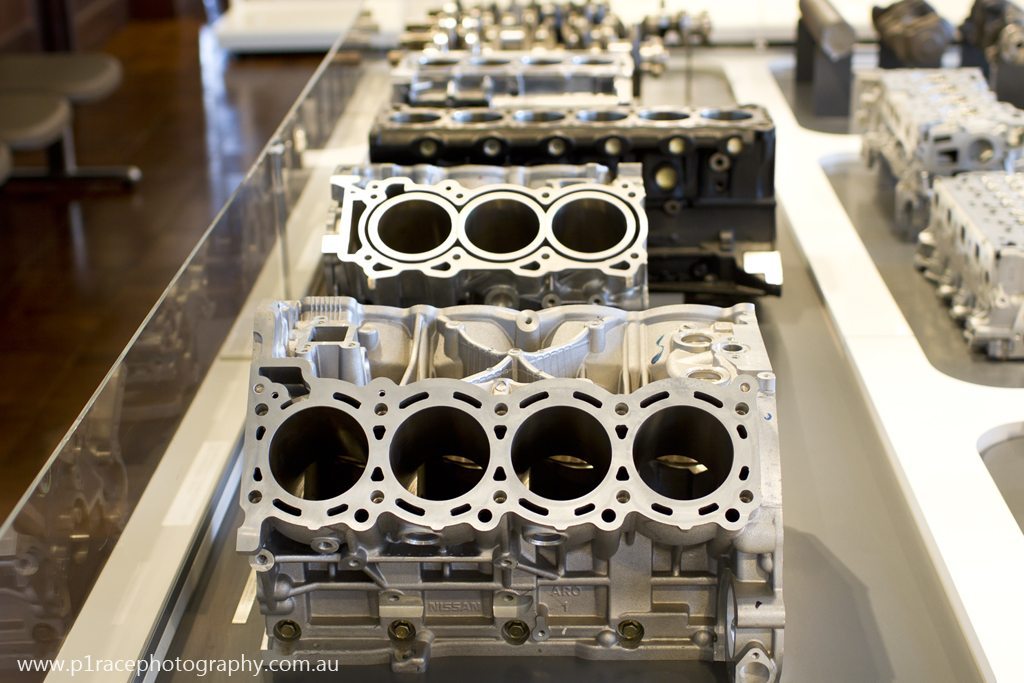

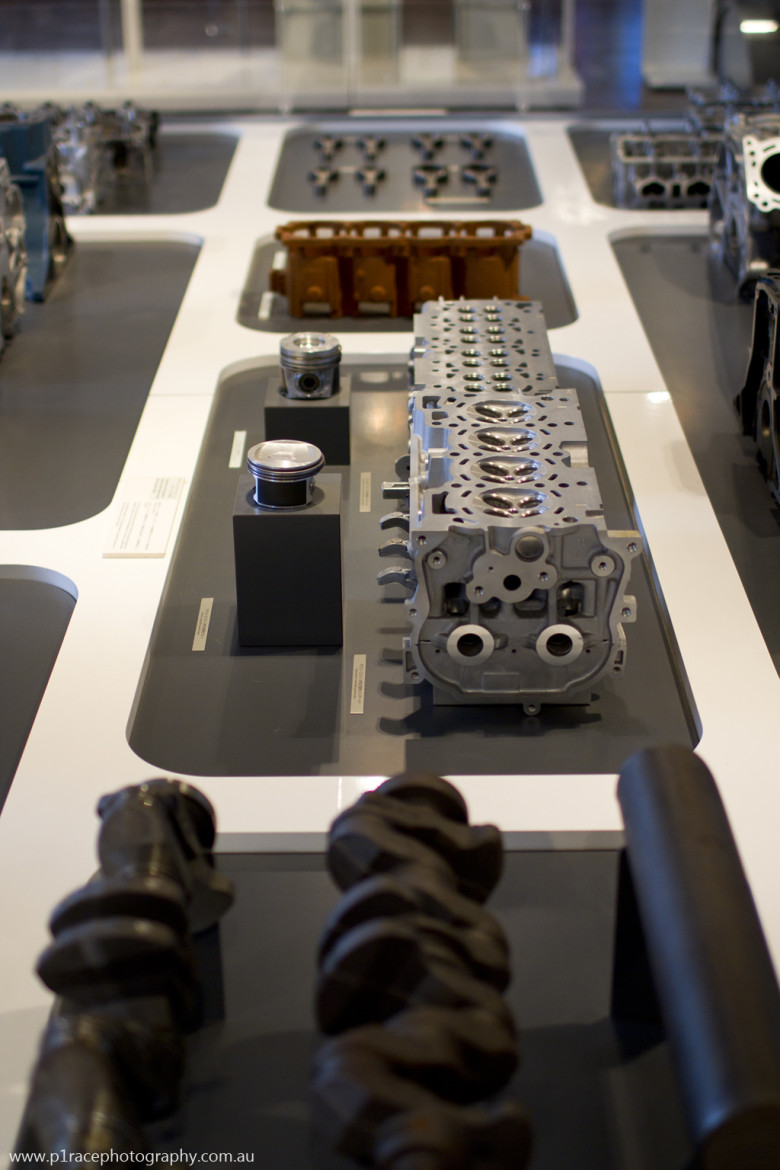

Across the hall I came to the final room of the museum – one dedicated to showing Nissan’s engine manufacturing evolution, one component at a time. On one wall, you had a case displaying some tiny early pistons and crankshafts, while below lay an assortment of more modern pistons.

It’s fascinating to see the small but significant changes in design that Nissan made with each generation and engine type.

In the centre of the room lay a huge area dedicated to the company’s blocks, crankshafts, pistons, heads and more. It was here, looking at the various pieces of Nissan’s engine history, especially the RB block and that of its current V6, I asked Maeda-san about the R35, and why it hadn’t kept with a straight six. Given BMW had kept its sixes, why couldn’t Nissan? Apparently, even if the company had redesigned the RB to meet emissions regulations, the weight and length of it would not have fitted with the R35’s goals. Ah well.

I also learned a few other things just walking around this display. Such as the fact Nissan sand-casts some of its blocks, making it surely one of the few mass producers to do so. Or that it forges its crankshafts. I also learned that, contrary to most race engine thinking, an open deck block can be just as strong, or stronger, than a closed deck one, as long as the design and casting process is right. Indeed, thanks to Maeda-san, I learned more in one day about engines than I had learned in years beforehand. It’s a powerful testament to the man and the museum. If you speak Japanese, I strongly suggest a trip to see what you can learn, too.