The dust of Dakar is settled, so why not open up some old wounds?

It’s actually best to start out by saying that “Fuelgate” is not the biggest story of Dakar. The thing that makes it so interesting is it being the least talked about story. Though to be perfectly honest, it has also been talked to death… just not in the wider media. Within the buzzing control rooms of Dakar race direction, and within many a European newsroom, there was much to be said about Honda’s inexplicable mistake. The press did make mention of it… but then it faded.

When it happened I was left dumbstruck, and I am still surprised there wasn’t a missing persons report filed somewhere between Buenos Aires and Japan. Heads will roll within Honda management no doubt. The rulebook is cut and dry: you cannot leave the race course in a neutralization zone. The factory Honda’s did, and they were penalized 1-hour each for the infraction. The only thing that saved them disqualification was they were seen by dozens of other teams, refueling at a local petrol station. It couldn’t have been deliberate or they would not have done this in plain sight. The 1-hour penalty was actually considered lenient by some.

If you are dying to know, a neutralization zone is basically a part of the race course where you stop racing. It’s like when you are beating up your little brother, but then your mom looks over so you pretend you are hugging. There is a speed limit and you need to behave like a road user in most cases, usually because you are going through a town or an environmentally sensitive area. In this case it was a town, and as I already said the HRC riders peeled off to refuel.

You can either decide they were running a little low on fuel due to a miscalculation (you only refuel in the refueling areas, they are marked on your road book), or you can decide the team boss was a cunning devil and sent his riders out several pounds light of fuel to give them an easier ride. If you search the enthusiast forums, your belief it tends to center with whether you like red or orange more, not which story has more merit.

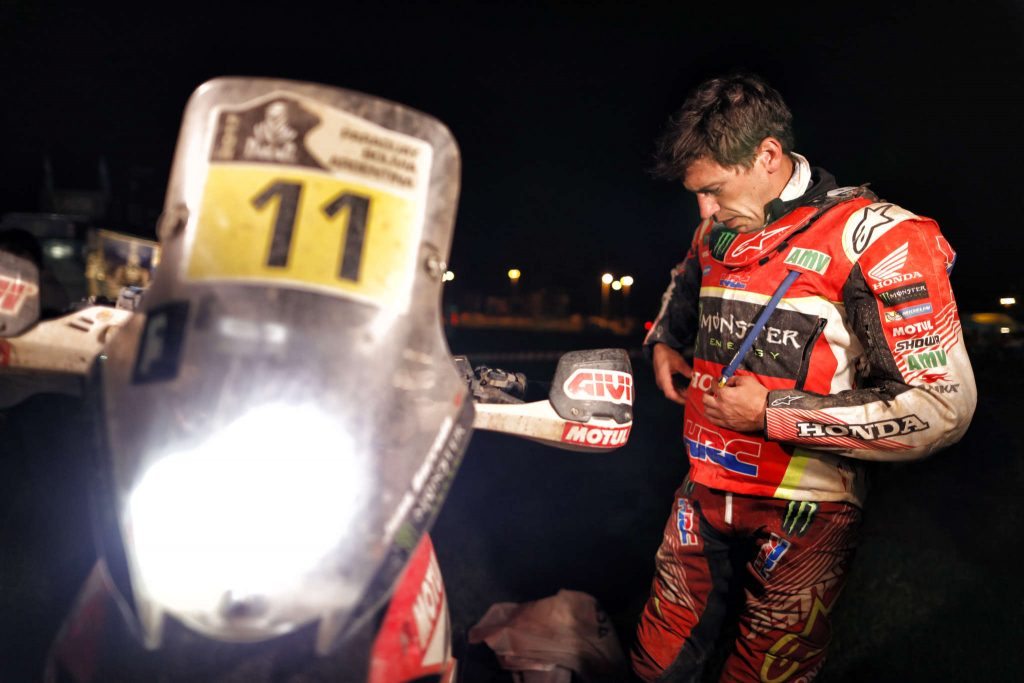

I can tell you this much: Honda isn’t likely to miscalculate fuel consumption for its factory team. It also wasn’t one of their riders who received the penalty. Joan Barreda, Paulo Goncalves, Michael Metge and Ricky Brabec all took an hour penalty straight on the chin. Pow.

Maybe they couldn’t store enough fuel to make it? An interesting theory if not for the dozens of privateer Honda’s trundling past as the factory bikes refueled. Combine that with the existence of portable fuel bladders and, at this point, too many years of math and design technology, and you have a story for the ages. “Remember that one Dakar when Honda totally blew it by…”

Suffice to say, Honda’s choice to protest the penalty nearly a week later was considered poor taste by many. Then again, KTM’s protest of the 1-hour penalty was considered poor taste by many as well (they wanted 3-hours). But as I already said, Honda could have been disqualified for leaving the course in a neutralization zone. That is how easy it is to follow the rule: they don’t expect people will break it. Honda cited a 2016 incident with “Mr. Dakar” himself Stephane Peterhensal, who was investigated for refueling in a neutralization zone in his Peugeot but cleared of any wrongdoing. It didn’t fly. Honda’s penalty stood.

KTM’s Sam Sunderland took an airplane back to Dubai with his 1st place Dakar trophy, and Honda had to fit a load of sour grapes in with their CRF450’s. The real shame of the story though isn’t Honda of course, they have a management team who finally had winning riders and a reliable bike, yet they couldn’t create a simple race strategy. The shame is that Joan Barreda and Paulo Goncalves both ran times within one hour of Sunderland’s winning time of 32h 06m 22s. Pulling that off even after being given the demoralizing penalty early on shows how determined they were and how well the bike was working.

But the drama will certainly get people tuning in next year to see if Honda can put everything together. It’s not like KTM is short on speed or talent; there is no reason to believe Honda will simply win next year without a penalty. They just seem to have an acute case of “blowing it.” This, despite changing their team management. Interestingly, their 2016 team manager, Wolfgang Fischer, managed the maiden effort for Hero Motorcycles, who basically used the Speedbrain Husqvarna, with updates. That team managed to land rider Joaquim Rodrigues in 12th overall.

If you aren’t familiar, Hero Motorcycles is an Indian manufacturer mainly known for frumpy mopeds that keep the country in motion. German company Speedbrain is probably not familiar either, yet their efforts should be. They are behind some high performance offerings for BMW’s and actually were the Husqvarna rally team for a few years, winning several Dakar stages in 2013.

They managed the Honda Dakar team as well, as I mentioned, and now they run Hero colors, and run they did. 12th overall and, although it may not technically be Speedbrain’s debut at Dakar, when partnering with a new company from another continent, there is definitely some adjustment. It is certainly better than the results of Hero’s partnership with Erik Buell, which bankrupted his company after Hero reneged on a promised infusion of capital.

From China With Love

The hat tip certainly went to Hero, and at the other end of the spectrum the jeers went to Zongshen. The Chinese brand gets kicked whether they are up or down, mainly because of the stigma associated with Chinese products. They entered five machines in a seriously brave attempt at the Dakar, with a confusing and basically non-existent marketing campaign. We were left to guess at what was some sort of 450cc bike that wasn’t a copy of a Yamaha (as previous machines were panned for being), and unknown riders and management would take them to a finish. Or to be accurate, unknown to people outside of China. Rider Willy Jobard was the only name I had heard of, and only vaguely.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0SU__125jgg

The result, from a PR stand point, was a disaster. The bikes on the starting line looked different than the ones in the teaser reel, and each other, hinting at ongoing development (or hail Mary problem solving). Personally I took this as a good sign. This is called “seat-of-the-pants testing” in America and once upon a time we all thought it was cool. You showed up with what you had and you ran it until it blew up, then you made the blown up parts better. That’s actually how we got these bland and lifeless road cars. Race teams broke everything so many times, now engineers can make a flavorless wonder. Damn.

Wasn’t I talking about Zongshen? Right then. Four of the five machines failed to make it through Stage 02, the first actual stage. Two seemed to be from navigation errors, but the others were possibly failures. Rumors swirled about crashes and navigation errors and you can take your pick. Zongshen actually replied to my inquiry and the word I got I will share in a moment.

The only survivor from Stage 02 was Thierry Bethys of France, who appeared to be a privateer until I found his Facebook page and stumbled through the only updates I could find. He was left off some of the official press, and his own press was in French, meaning you had to infer he was on the team because he was on one of the bikes. Hey, if you have a Zongshen at Dakar, you outta be welcome to hang out under the factory tent regardless. In reality I believe he was left out of the cryptic email response I received from Zongshen because he was not running their experimental RX3 engine (the entire reason for their pursuit of Dakar glory). I could not confirm this by press time.

Sadly, on Stage 04 Thierry’s bike suffered problems siphoning fuel between its two tanks, causing a loss of power. Thierry made repairs, but near the end of the stage he crashed, rupturing one of the fuel tanks. Splashing gasoline onto a hot engine is no good. Thierry was okay, but Zongshen’s maiden Dakar was now literally up in smoke.

Now, as I mentioned, I got a bona fide reply from “Sean” at Zongshen. The translation makes it exciting to analyze– like I’m part of a spy novel or something– but there is some solid information. First, Zongshen are some bona fide John Wayne style people. They built this engine and were definitely not finished testing it, but took it to Dakar to let ‘er rip anyways. They plopped Jen Hsien Chi in one of the saddles. A well known singer and TV star in China, Chi suffered three falls during Stage 02. He came together with an ATV, then got stuck in the giant mud hole that swallowed half the trucks as well as several bikes, and then found an unforgiving enough object in the form of a tree. A helicopter ride later showed no serious damage, but the bike, and Chi’s Dakar, were done.

Willy Jobard fared better but met the same fate. The Frenchman broke his foot in a crash and was out of the race in Stage 02 as well. Now we are left with Zhao Hongyi and Zhang Min. The pair are experienced racers within China, but this was their first time racing abroad. Min ran into charging system troubles on the bike during the entirety of Stage 01 and 02, according to Zongshen’s marketing man “Sean.” Hongyi stopped to help and, with both of them losing a lot of time, fell victim to pressure of making up time. It wasn’t a crash that took him out, but a failure in the fuel system.

I seem to be in the tiny camp of people not laughing at the effort. To show up and fail that spectacularly is impressive. I hope they come back. If it were an American team stuck with limited access to resources and information, showing up and having at it by the seat of their pants, we’d be raising a can of piss-warm beer and cheering them on. To put that much at stake on an international stage, and do so much of it in-house, deserves credit. I can’t help but admire their moxie.

And to cap it off, there was nothing but pragmatism in the tone of the email I received. The biggest disappointment overall was that they have to find another way to test the new engine, because they didn’t get enough race time at Dakar. When asked if they would return, the answer was equally pragmatic. “After the 2017 Dakar, we know we still have a lot of experience to catch up with, and we are not sure yet whether we are ready for the 2018 Dakar. It is [an] important thing for us that matters not only [for] the whole team but also [for] the engines. All we understand is that it is a definitely a complicated task to finish a Dakar [Rally] Race.”

Indeed.

Hero Motorcycles bought a race team and a race bike. While the effort is commendable and earned a lot of press, Zongshen’s failure will yield far more information in how to managed a rally team, build a rally bike, and market an international race than Hero’s approach. The power of failure should not be underestimated.

And There You Have It

Ten other stories come to mind of course, but there is simply no space. I have already filled up volumes about Lyndon Poskitt’s fantastic adventure to second place in the Malle Moto class and Toomas Triisa’s cyborg-like win in the class. Lyndon actually made the Dakar a stop off in his round and round the world sojourn, Races To Places. He has been continent hopping for three years now, hitting up rallies large and small on his own bike, Basil. KTM and Motorex helped him out for Dakar though with the 2017 model he used.

Dakar also brought the story of Anastasiya Nifontova, who turned out to be near-impossible to track beyond transponder times. The young Russian is a well known name due to the African Eco-Race, an event that tried to take the place of Dakar when it left the African continent for South America. Drawing privateer entries and being a purist’s dream, Anastasiya was a front runner there.

In the Dakar she struggled mightily with the heat as well as navigation. Several times she appeared to miss the cut off and be stuck on course well into the night. I thought she would be disqualified, only to wake up the next morning and see her name at checkpoint 1. Hurray! She may have stumbled with running dead last much of the rally, but at one point the entire field made a navigation error.

The early riders mistook a mud hole for a fork despite the roadbook saying the split was further ahead. Despite seeing 100 tire tracks heading off to the side, Anastasiya trusted her navigation skill, picking up dozens of positions in the process. In the end she finished 75th overall, her infectious smile being hard to miss during celebrations.

The stories just keep coming. but if you’ve read this far you are among an extremely small percentage of people left on the internet. Because with the sheer size of Dakar as an event, this is just a look at some of the unique stories to pop up this year, and it only covers the bike class. The story of just the top riders alone requires more space than this, so it is best to give the brain a rest and let the highlight reel take us through the essence of Dakar 2017: Bike category.