If you have ever traveled across Nebraska, its obvious that we have no mountains. But even with no mountains, Nebraskans have been coming to compete at Pikes Peak for decades.

In fact, two drivers from Nebraska won overall in 1921 and 1922. Those two drivers were King Rhiley of Oshkosh Nebraska, and Noel Bullock of North Platte Nebraska. Rhiley was a circle track veteran who had raced in Nebraska for years.

He won the 1921 Pikes Peak Hill Climb with a “fast” time of 19:16 in his Hudson Super-Six Special. Rhiley also won over 50 oval track races throughout Nebraska, and was a huge threat for many years on the peak.

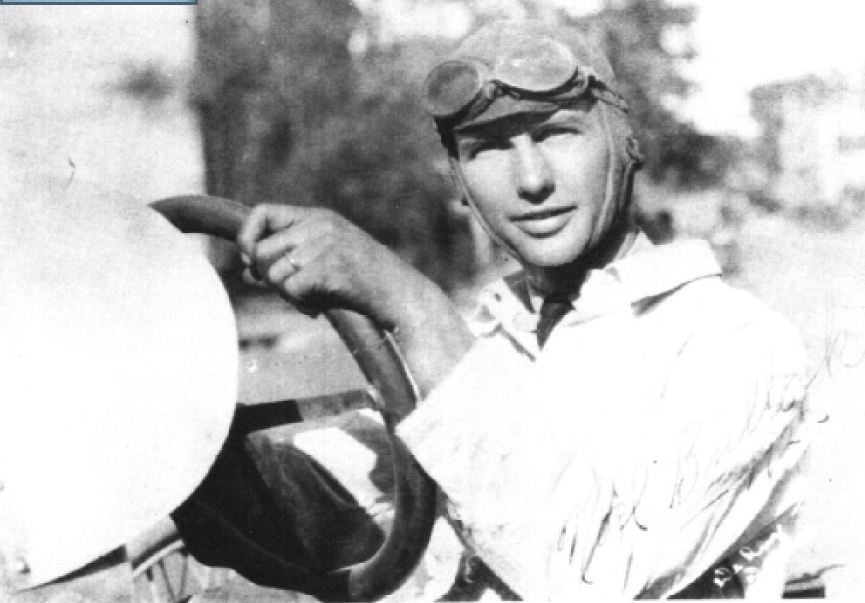

The year 1922 saw the coming of a young driver named Noel Bullock who had little money, no factory backing, and an attitude of never giving up no matter what the circumstances.

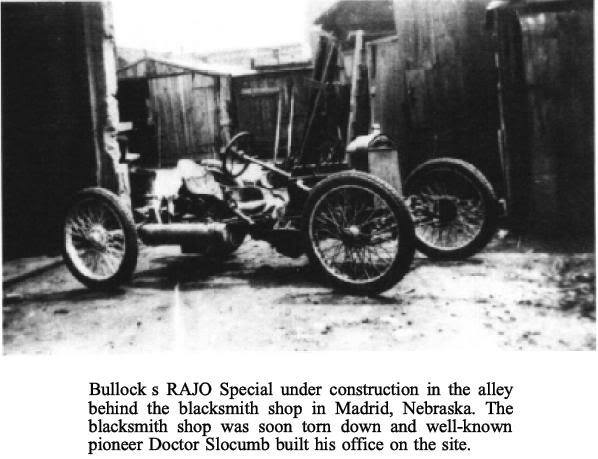

His car, the “Tin Lizzy”, started life as a circle track race car in 1918, winning several races before coming to the peak. When Bullock showed up to the Broadmoor Garage (where all cars were kept at the time), people stood astonished that anyone would be crazy enough to race a vehicle that rickety up a mountain road. Before Bullock showed up, the race was dominated by heavy and sturdy machines such as Hudsons, Packards, and Mercers. Some were factory backed, and most had a pleasant appearance too them. No one had ever seen anything like Bullock’s tiny, modified Ford Model T do anything special at Pikes Peak.

His car, the “Tin Lizzy”, started life as a circle track race car in 1918, winning several races before coming to the peak. When Bullock showed up to the Broadmoor Garage (where all cars were kept at the time), people stood astonished that anyone would be crazy enough to race a vehicle that rickety up a mountain road. Before Bullock showed up, the race was dominated by heavy and sturdy machines such as Hudsons, Packards, and Mercers. Some were factory backed, and most had a pleasant appearance too them. No one had ever seen anything like Bullock’s tiny, modified Ford Model T do anything special at Pikes Peak.

When it came to practice and qualifying, Bullock arrived too late to be in Thursday’s time trials. So, on Saturday morning, Bullock ran the car up the mountain for his first and only time before the event started on Monday. One thing about the race that has changed since the early 1900’s is when the race is run. Back in 1922, race day was on September 4th, so conditions were cold and overcast. Weather was still a factor however, and hail, rain, and snow had hit the top of the course hard the night before.

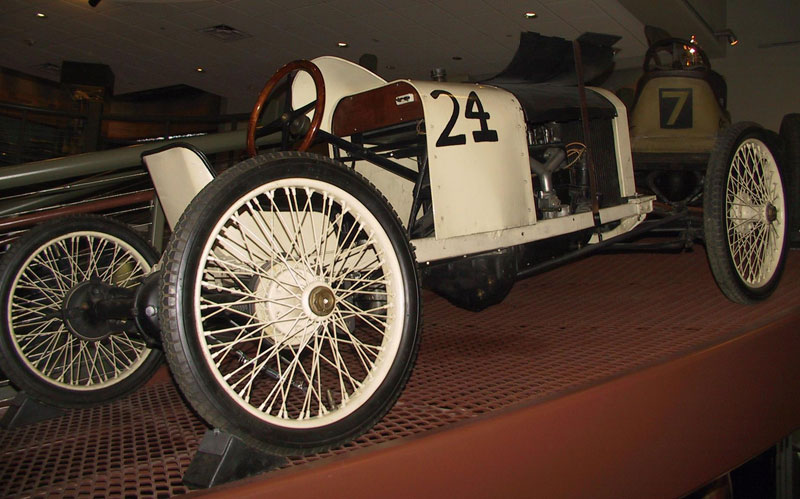

When Bullock pulled up to the starting line that morning, officials realized that he had no number on the car.  Bullock said: “Haven’t been given one”. Since he was such a handy guy, he found some black enamel in his tool box, and painted with his finger the number 24 (his starting position) on Tin Liz. While he waited at the start, no one was getting anywhere close to the record of 18:24 set in 1916. After waiting for two hours, it was finally time for Bullock to show the world what a hand-built car, and a young Nebraskan was capable of doing.

Bullock said: “Haven’t been given one”. Since he was such a handy guy, he found some black enamel in his tool box, and painted with his finger the number 24 (his starting position) on Tin Liz. While he waited at the start, no one was getting anywhere close to the record of 18:24 set in 1916. After waiting for two hours, it was finally time for Bullock to show the world what a hand-built car, and a young Nebraskan was capable of doing.

As Bullock climbed up Pikes Peak, he amazed spectators with a driving style they had never seen before. He was sideways, throttle wide open around turns, and had a few close calls with the 2000 ft drop-offs the peak is known for. His crazy driving style, and lightweight Tin Lizzy, was enough to set a very fast time of 19:50 and beat the entire field. Spectators and race officials alike could not believe what they had just witnessed. As Bullock got out of his car, he was smiling from ear to ear. Race officials wondered how on earth could a car like that beat all those high-powered, heavy-weight machines? Bullock’s win, that was very well deserved, did not go over well with race organizers.

As Bullock climbed up Pikes Peak, he amazed spectators with a driving style they had never seen before. He was sideways, throttle wide open around turns, and had a few close calls with the 2000 ft drop-offs the peak is known for. His crazy driving style, and lightweight Tin Lizzy, was enough to set a very fast time of 19:50 and beat the entire field. Spectators and race officials alike could not believe what they had just witnessed. As Bullock got out of his car, he was smiling from ear to ear. Race officials wondered how on earth could a car like that beat all those high-powered, heavy-weight machines? Bullock’s win, that was very well deserved, did not go over well with race organizers.

The next day, press from all across the country published the story on Bullock beating the best of the best factory cars on Pikes Peak. That type of publicity aggravated race organizers because that wasn’t the image the hill climb had been known for. It was supposed to be a race of the top machines and companies battling for the Penrose Trophy, or so that’s what they thought.

So, in 1923, when Bullock and others with home-built cars tried to enter, they got turned away. Just 9 days before the race, the hill climb implemented a new set of rules that each car could not be any lighter than 1600 pounds. Bullock, and his friend from Nebraska (King Rhiley), added weight to their cars and thought that everything was fine. It wasn’t; the hill climb stated that the two had participated at a non-sanctioned dirt track race in South Dakota in July, and would no longer be able to compete in the 1923 Race To The Clouds.

Since the hill climb started, Nebraskans have been coming to compete. Maybe it’s because the event is right next door. Maybe it’s the fact that Nebraska doesn’t have any major racing venues or events, or maybe its because Nebraska has a lot of great drivers who want their shot at glory. Whatever the reasons, we Nebraskans have shown that we have the talent to win at Pikes Peak.

Over the years the rules changed, and the hill climb became more of a David vs. Goliath event. This created much more interest among the public and competitors because people wanted to see if the little guy could take on the big guns. In one way or another, this is still very true today. Some teams spend millions of dollars in technology, engineering, employees, and advertising, trying to be king of the mountain.

The majority of competitors though compete with money out of their own pocket, usually with little sponsor money. Many volunteers help out because they love the determination of the drivers, and also want to show it doesn’t take $$$ to accomplish a mighty goal. That reason is why the Pikes Peak International Hill Climb is America’s last great automotive race. The spirit that Noel Bullock had in the early 1920’s lives on, and will forever. – Colin Brandt

Today the Tin Lizzy is on display at the El Pomar Foundation Carriage Museum in Colorado Springs.

Today the Tin Lizzy is on display at the El Pomar Foundation Carriage Museum in Colorado Springs.

Sources:http://www.nwvs.org/Technical/MTFCA/Articles/1405PikesPeak1922.pdf

http://www.omaha.com/article/20110512/SPORTS/705129700

http://www.jalopyjournal.com/forum/showthread.php?s=1d13809dfdfb54456a8bb652e2fead7d&t=529700

http://www.narhof.com/ind-detail.asp?DriverID=19

http://edgeoftheplanetadventures.blogspot.com/2010/12/tin-lizzie.html

[doptg id=”58″]